Jessica Lynne on Zalika Azim’s ‘in case you should forget to sweep before sunset’

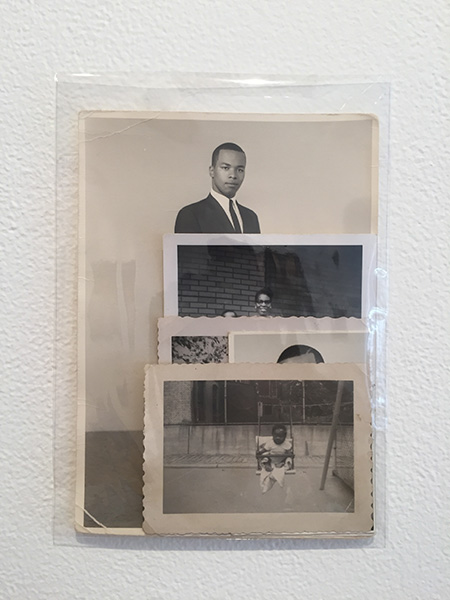

A place where the soul can rest (visiting Aunt Louise), 2019

I have always loved the way bell hooks celebrated photography’s role within Black Southern homes. In Art on My Mind, a book that continues to linger with me, hooks acknowledges that within the domestic interiors, photography often takes on a ceremonial role, enshrining its Black subjects with a perpetual dignity. As I have learned, it is often the matriarch who uses a narrow mantle to proudly display that one photograph of the aunt captured wearing her favorite Malcolm X t-shirt, her grin wide as she points to the late Civil Rights Leader’s face while sitting in a white dining room chair. Sometimes we gaze at the photograph mounted on the hallway that leads to the bathroom that features your eldest cousin in his best Easter suit from three years ago because, as grandma had reminded you, he looked so sharp that day. Other times, grandma will leaf through an old photo album from her girlhood, stored in the attic, to find that photograph in which she and her girlfriends slyly pose for the someone off camera.

These vernacular images become embedded with meaning beyond what we immediately see. How do we reconcile ourselves to their subtexts and subplots, the invisible stories from which they emerge? How do we, as Tina Campt suggests in Listening to Images, listen to them in order to unfold these subtexts and subplots? This question becomes especially important as we consider how these images have traveled through time, passing through the hands of generations of kin. Each encounter introduces new moments of interpretation.

I am reminded of Emmanuel Iduma’s words in A Stranger’s Pose: Photography is a charismatic medium. Sometimes it takes five decades for a photograph to unravel itself.

So, what does it mean to come to these photographs and their (psychic) landscapes in new contexts and eras? These questions emerge in Zalika Azim’s exhibition, in case you should forget to sweep before sunset.

Azim, who grew up in Brooklyn, follows her paternal traces of these remnants back to South Carolina, as a careful, if not spiritual, pilgrimage to a place that is of her lineage but from which she is still removed. How to describe a relationship with a place that we have known, primarily, through the memories of others?

I have often thought the American South to be the soul of Black America. A site in which we can see the origins of a cultural lexicon that spread north and west, in large part, via The Great Migration, even as it remains a pivotal nexus within the African Diaspora. As Black folks dared to escape the violences of the region in great numbers as the twentieth century rolled on, they followed the train routes away: Mississippi to Chicago and Milwaukee; Louisiana and Texas to Los Angeles and San Francisco; South Carolina on up to Washington D.C., Philadelphia, and New York City. If you look and listen closely, you can see, hear, feel the South as it pulsates far beyond its geographic boundaries.

Forging a new intimacy with an ancestral home, Azim approaches this task through a sacred communion that includes images made by her late grandmother Mary E. Lemons (It is always the matriarch, isn’t it?). Azim’s reconciliation contemplates the tools needed to close a proverbial loop that is defined by an unknowing and she undertakes the task of unraveling blood memory by collapsing, merging, and layering temporalities and materials—in which memory, text, and the photograph itself are all included.

Sunday Portrait (Habibi), 2019, is a 5”x7” image comprised of five smaller black-and-white archival images that have been layered on top of one another and covered with an archival photo sleeve to collectively become a familial homage to a Black cool. The photograph most clear is the image of a toddler in a swing. The last and largest image is of a sharply dressed young man wearing a suit whose likeness appears as a bust due to the manner in which the other photographs have been stacked. I have known these images in my own way, a particular kind of inherited visual code that denotes the occurrence of a significant occasion, play, or a rite of passage.

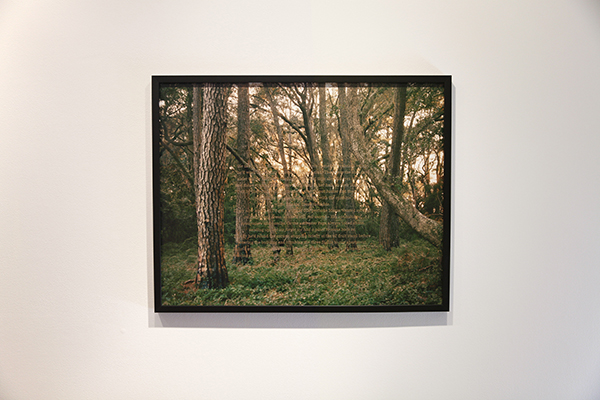

I know this too: this textual intervention, this minding of the gap, if you will. This nonlinear grappling with an intangible inheritance. To make sense of who we are as Black people in the U.S. and from whom we have been made, we might also have to conjure our haints. A gesture of significance that is taken up by Azim in To speak of a lush hot blooded land, to the dispossessed, too busy to visit, 2019—a striking image of a forest at sunset on Edisto Island, South Carolina that becomes a plot on the map that Azim is creating as she calls forth familial connections:

He use to bring those pretty yellow flowers home on weekends when

he’d work long hours uptown at the jazz club. They were the kind my

sister Carrie said reminded her of the first time she laid eyes on Lina,

and those evening trumpeters she placed in her hair on their last night.

I’d sit by the window for hours, long after I’d put Junior and them down,

watchin’ as the street lights flirted with the curtains

while thinkin’ those thoughts.

Every now and then I’d get a whiff of that perfume Mama wanted sprayed

On her resting dress, so she’d still feel warm—like sandalwood,

newspapers and vanilla. Or the saltwater Papa always joked about

sending up, lest we forget we had a place to come back to.

Finally he’d round the corner, stopping briefly at the ol’ fruit stand before

entering the building and climbing the three flights to our apartment.

In he’d enter, kicking his shoes off at the front door, before whispering his

evening greeting which nowadays sounded more like a dispossession than

the first few notes of a hymn.

Is this not what it means to embark on pilgrimage?

Like Azim, I am wrestling with my origin (story). I say this to her the day we meet for coffee and she greets my admission with that familiar Black women affirmation—a deep, guttural yes—an embodied spiritual code itself. And as a Black Southerner, I understand the desire to wade through memory and re-memory in the effort to untangle my relationship to a place that remains more complex than it is often considered to be.

Photography, for Black folks, carries our many knowledges even as it makes space for us to expand upon, revise, and reckon with these ways of knowing. With in case you should forget to sweep before sunset, Azim steps into this work, this infinite unraveling (can this task ever be really be finished?), creating, as an exhibition, her own shrine to the Black Southerners, in particular, of whom she is part.