2016 Annual Juried Exhibition at Baxter St/Camera Club of New York Introduced Three Photographers Selected By Mickalene Thomas

Curated by Mickalene Thomas, 2016 Annual Juried Exhibition at Baxter St at Camera Club of New York introduced lens-based works by Travis Brown, Danielle Eliska Lyle, and Marc Ohrem-Leclef, tapping onto prevalent contemporary issues such as gentrification, economic injustice, and racial and sexist prejudice. The artists selected by Thomas through an open call exhibited their works at the Organization’s gallery located in Chinatown through September 3rd.

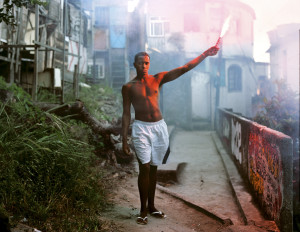

Lyle’s Female Protagonist: Unveiled was a fourteen-minute single channel video of five African-American actresses weighing on patriarchal system and ways they handle with sexism and racial presumptions on daily basis, offering an intimate viewing experience, supplemented by mostly black and white photographs of the subject women. Ohrem-Leclef’s arresting photography series, Olympic Favela, traced individuals forced to leave their homes in preparation for construction of 2016 Olympics sites in Rio de Janeiro. Thousands of locals, whose lives are swept away by inhumane governmental policies, seek for solution, as embodied through torches they lift up while piercingly staring at the artist’s camera. The first place winner Brown juxtaposed a photo-installation display, utilizing his variously sized frameless photographs to strengthen the impact of his subject matter. Scenes from West Tennessee including portraits of locals as well as details of interiors and landscapes narrated tales from a land that seems so far away yet nearby. On the occasion of 2016 Annual Juried Exhibition, I asked each artist two questions enveloping their bodies of works in the exhibition.

Danielle Eliskla Lyle:

— While talking to your camera, these actresses are incredibly open and physiologically exposed. How did you build such trust with your models? Was this mutual confidence built over time?

It’s interesting. I knew these women but I wasn’t close with any of them. I’ve worked with them in grad school or theatre performances post-grad school. One actress, the amazing Sandra Daley-Sharif, was a founder and dramaturg for a Black playwrights group I was a member of. That’s the longest standing relationship. Another actress, Tashion Folkes, we met the day of the shoot. So we all had professional connections.

When I sent the e-mail detailing what I wanted to do with the project, I honestly wasn’t sure what responses I’d receive. I thought I would get one or two responses. But I had eight responses; other actresses (about seven more) from social media saw “sneak previews” of photos in their timelines and became very intrigued by the project and wanted to be a part. Unfortunately, I had to turn them away because my idea for this project was to preserve intimacy. But I must say, I was beyond grateful that these women were willing to share themselves in such a personal vulnerable space. Yes, they are actresses and in front of cameras all the time. But that’s work. This space where we existed together was very intimate. It was in their homes—most were early morning shoots, natural light for dramatic effect. I asked them all to wear little to no makeup and dress in some form of white, if possible. I didn’t prepare them by sending the questions because I wanted it to be as natural as possible. I had a feeling they wouldn’t shield anything because they all believed in the project. They were all like, “GIRL! YES! This is something I am interested in doing.” That let me know that this body of work needed to be done.

I knew the actresses would dwell in a very exposed, unguarded space when asked the questions for the moving image aspect of the series. So, I wanted the photographs to showcase their beauty in juxtaposition to their unveiled insecurities they confessed on video. I wanted them to hear their words but see themselves totally different from that. That is why I chose the dramatic lighting, the intimate setting. These women naturally posed as you see them. I didn’t have to do much coaching. These poses were of their own volition. And they were all so naturally regal.

— How was your experience coping with sexism towards women, especially for black women? How has way of coping changed/improved after working on this project?

“Female Protagonist” series didn’t begin as a project for black women. It just ended up that way, which I believe was divine order for this body of work. GOD is my creativity’s greatest influence. I just go with the flow. The series was originally a project for women. I sent that e-mail to actresses of various cultural and racial backgrounds. I had two actresses—one Asian decent, the other Caucasian—who wanted to but couldn’t be a part because they were working out of town in theatre productions during the time of the shoots.

A lot of my writings as a screenwriter and playwright have to do with the Black Diaspora and women protagonists, which are generally Black in my stories. I wanted this photography series to be a little different. I wanted to see for myself the likeness of womanhood, no matter the color. The message I wanted to convey still worked successfully. These women came from mixed heritages (like myself), yet they all questioned whether or not they were enough. I found that to be intriguing.

To answer your question of how has my way of coping changed or improved—it’s not a one-time deal. Daily, women find ways to be freed from the opinion of men. And I mean, “men” in a sense of mankind and/or western civilization that hold us captive. We cannot change how others think of us. They must change their own thinking. But if we exist free, then nothing will be impossible to us.

Women deal with sexism daily. As my mentor would say to me about the struggle, “same river, different current.” And it rings true today in so many aspects. It’s baffling!

Women—we just deal. Black women have what I’ve heard called, “two strikes”—we’re black AND we’re women. But those aren’t strikes—that’s power. So the answer to your question for this series must include racism and sexism. The world will always see the Black, then the woman. There is no escaping it, nor do I wish it. We are not here to adapt to a climate that is created by white, privileged men (or women). We are here to exist in our beauty and power and innate prestige, overshadowing the propaganda created to make us feel inferior. We are majestic. The world makes room for us when we realize that—just as it made room for the highest mountains, the matchless pyramids and the deep blue seas. Once we see ourselves the way GOD sees us, our presence will demand the world to make room for us.

Marc Ohrem-Leclef:

— One reason Olympic Favela is so strong is the fact that your figures are holding torches, while piercingly staring at your camera. Holding of a torch has many interpretations from seeking help to claiming victory. Did you plan this component from the beginning or did it happen organically?

I developed the concept of photographing my collaborators holding torches early-on in the process of working on “Olympic Favela”. I wanted to use portraiture in a traditional way — my subjects posing in the communities, often in front of their homes marked by Rio de Janeiro’s housing authority SMH for removal — to humanize them and show them in a value-free environment. And I wanted to attempt a secondary approach in portraying the favela residents in a moment of strength and pride, rather than showing them as passive victims.

I used Image Atlas to research universally recognized imagery as far as gestures go relating to keywords such as ‘defiance’, ‘victory’, ’emergency’, ‘protest’, ‘home’ and ‘eviction’. The gesture of the raised arm and fist—whether it is holding a sword, a flag, a smoke flare or the torch—creates a beautiful cross section of the hopes and fears the residents expressed in the interviews and conversations we conducted over four years of the project. In short, the gesture plays on all the contradictions I feel when I think about the ideals and the realities of the Olympics.

But before actually suggesting to them to pose with the emergency torches, I had to navigate warnings of lighting the torches in still often unsafe communities and winning the residents trust first . But my research paid off, my collaborators understood the idea immediately and loved the opportunity to be shown in this moment of strength.

— Gentrification also means the disappearance of the culture, identities and memories that shape the local community. This narrative unfortunately is a part of New York as well. How do you see the comparison between two cities in this sense?

“Olympic Favela” visualizes the issue of forced evictions directly related to the mega events of the World Cup (2014) and the 2016 Olympic Games. While gentrification plays into the urban changes taking place in Rio de Janeiro and many urban centers worldwide, the difference between the upgrading and modernization of favela neighborhoods in Rio and the complete destruction of communities remain distinct and important.

While gentrification is normally based on a gradual influx of capital flowing into a neighborhood and changing its culture and literal landscape, the communities I worked in are often erased or dramatically impacted (in a short amount of time) through the direct influence of state power in the form of city and state governments, which in a very short amount of time grab land that in many cases belongs to the people living on it.

The loss of ‘home’ in the sense of place, actual home, the community and culture produced by it may be a similar result in the end; however the lack of democratic process and input from side of the favela residents, combined with the speed with which the evictions relating to the Olympic Games happen, separate the issues in my experience somewhat. I strove to address the urgency of these factors in the images of residents holding emergency flares.

Travis Brown:

—Your Cashin’ Out series depicts West Tennessee through portraits of locals as well as detail shots of interiors. How did you build a balance between individual portraits and these details?

I like going to public places such as baseball parks, diners, bars, etc. to meet people. I find the energy in these places to be electric, so I make detail shots to represent them. The image titled Buccaneers for example symbolizes the passage of time, destruction and beauty. It could be said that these characteristics are similar to the way people portray the South. The balance ultimately comes out in the editing, whether it is for a book or sequencing for an exhibition.

— What was your interaction with the community there like? Did listening to their stories and knowing about their biographies affect your approach?

I visited West Tennessee for long periods of time while working on Cashin’ Out. I had a lot of interaction with different types of people. In some ways it was easy for me to connect with people since I am from Tennessee myself and I grew up with all the nuances of the South.

I don’t always talk to the people I photograph, I like spontaneity. I’m quite a talkative person so it’s not like I won’t speak to them at all, it’s just that sometimes I’m going to make the picture first and then talk. For the image titled Troy, I just started photographing without even asking him if I could take his photograph. He knew I was going to be photographing when he saw the gigantic “Texas Leica” aka Fuji GW690II around my neck, anybody would know what that represents. He was so proud at that moment because he had just finished installing a new engine for his Caddy so it’s not like he would have said no.

At other times, I really get to know people and spend a deal of time with them.

On one occasion, I got to work with the assistant district attorney for Shelby County. She thought my work was interesting and wanted to shed light on areas of her town that I might not be familiar with. She taught me a lot about her community. There was also a lady named Doreen who I met outside her church on a Sunday morning. I started speaking with her and gave her a ride to her home. I spent time getting to know her and she told me stories of her hometown of Memphis and how much more dangerous it has become.