A home for fleas, a hive for bees, a nest for birds

Thank you to Baxter St. for inviting me to come in as guest blogger for the next three months. I look forward to sharing some thoughts, musings, and artworks.

I was always a writer. That is, before I would ever have called myself an artist, I thought of myself as a writer. Writing came naturally for me. My father is a poet, my mother an architect and excellent writer. Somehow, though, I slipped into the visual realm and became frightened of writing. Frightened of how words would affect the images (I am always telling my students about how I believe viewers privilege text over image, how a photograph’s caption – even its title – becomes “truth” and the image almost an accessory, an illustration – but maybe it’s just me) and how explanation can make even the most sublime work seem banal. However, my yearning, my desire, for textual lyricism remains, an ultimate (likely impossible) goal of my own (visual) work. My artwork emerges (however obliquely) from “text” – that slippery word – and from poetry, most recently, H.D.’s 1916 book Sea Garden. I argue that there is a lyrical structure to my work overall, and a way of reading a particular work that might be similar to the reading of a poem. My most recent series, No Whiteness Lost and Waves, too, can be read as collections of poems, with threads, sometimes tenuous, going through the works, but with no answers given. One had better not try to read my work as prose, as it would be an exercise in frustration.

All of that said, I am pleased to be writing again. I hope to devote these posts to my muses, to larger ideas that I have been thinking about, and to exploring how they relate to my work and the work of other artists.

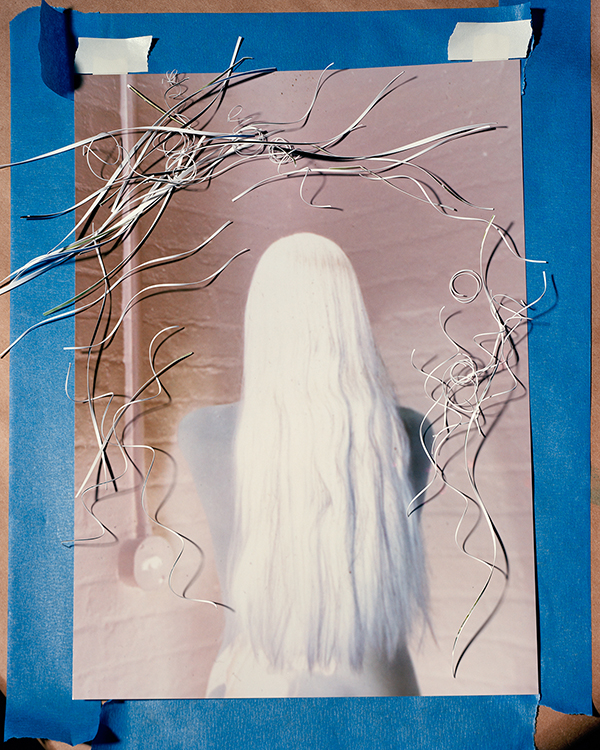

ABOVE: from my series Waves, this image is called Needles & Pins (Outs & Ins), 2015

I had quite long, blonde hair as a girl. Long, straight, smooth, thick-but-fine, whatever you want to call it, it went up-to-down with no detours, flaxen and waxen. I don’t remember loving or hating my hair, until just before my ninth birthday when it was lopped off – my entire braid, chop (I believe it exists, still, somewhere in that treasure trove of tiny drawers in my mother’s Tansu dresser). Whether the cut was my request or my mother’s didn’t matter – my hair was gone. I felt ugly, I felt like a boy. Even as a young girl (and not a girly girl), hair symbolized beauty, femininity, possibility to me. I did not cut my hair again, in any significant way, until I was a junior at Vassar, and we all cut our hair off. Whether in rebellion against beauty or the feminine or shampoo or straight culture (it was Vassar, it was the ’90s), it was gone, for so many women friends at that time. Some kept their hair short but I grew mine back out and now I have the (sometimes very) long hair for which many friends know me. Less blonde, some grays in there, but long. I get it cut twice a year. My son turns four tomorrow and refuses to get a haircut, loves to shake his wild blond mane. I guess it runs in the family.

I began making figurative work perhaps two years ago. My images had slowly evolved from landscape to photographs of objects to rephotographed and reconfigured photographs – self-portraits, portraits of friends and strangers, and found images, repurposed and rephotographed. Some men but mostly women. As I write in my artist statement for this series, Waves, “This is a a process of transformation, of transfiguration, an almost sacrilegious transubstantiation, the conversion of flesh and blood into image and that image back into sculpture, and the object back into a photograph.” Hair – my own and others’ – figures prominently in the work. Self portraits are inverted so the hair appears white, or lit so the hair appears black. Women’s hair obscures their faces, becomes a mask, overwriting/rewriting/concealing their identities. Hair is pulled through holes in photographs. Curled paper is arrayed over prints. I stress in my work that the images are not indexical – that is, they are not of what they represent; rather, they are meant to evoke feelings, to address reality in their removal from reality. This woman figure in all her iterations stands as avatar for the woman as artist, the woman as maker of life and object.

ABOVE: Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940, Oil on Canvas, 15 3/4 x 11″ (40 x 27.9 cm)

After she divorced Diego Rivera (following his tryst with her own sister), Frida Kahlo made this fantastic and compelling self-portrait, a renunciation of femininity. She swims in this massive suit (presumably his) and gazes with her characteristic intensity, at the viewer. One of my favorite parts of this painting is the sea of hair – like snakes – that fills the bottom half of the canvas.

ABOVE: Lorna Simpson, Wigs (Portfolio), 1994, Portfolio of twenty-one lithographs on felt, with seventeen lithographed felt text panels, 6′ x 13′ 6″

These wigs range from an afro, to braids, to blonde and waxen, to a merkin. By creating these lithographs on felt, Simpson builds a sensuous and luscious depth. In an oft-quoted interview of Simpson with Barbara Pollack in September 2002 ARTNews, “Turning Down the Stereotypes,” she says, “For me, the specter of race looms so large because this is a culture where using the black figure takes on very particular meanings, even stereotypes. But, if I were a white artist using Caucasian models, then the work would be read as completely universalist. It would be construed differently. I try to get viewers to realize … that it is all a matter of surfaces and façades.”

ABOVE: Hannah Wilke, Brushstrokes: January 19, 1992, no. 6, 1992 Artist’s hair on paper, 30″ x 22 1/4″

I recently came across these moving, simple sculptures or perhaps even drawings of Hannah Wilke’s, part of her work documenting her battle with cancer. As she lost her hair due to her cancer treatment, she created these “brushstrokes,” each dated with the day she lost the hair.

ABOVE: Mika Rottenberg, Still from: Cheese, 2008, Multi-channel video installation, Dimensions variable

I saw Mika Rottenberg’s Cheese at the 2008 Whitney Biennial. A narrative work, Rottenberg combines sculpture, video, and machinery within the framework of a crude shack (her video works often take place in confined spaces). Cheese is a fictionalized account of the Sutherland Sisters, famous for their cure for baldness, using women she had met through a long hair club. She tells Judith Hudson about her experience working with subjects/performers in a 2010 BOMB Magazine interview (BOMB 113): “I think these people who work for me empower themselves by renting out their oddities, like the long-haired ladies from Cheese. I usually use a verbal contract that is based on trust. I have a lot of respect for the people I hire; for example, the ladies from Cheese. But, on the second day of shooting, it was really hot and their hair got a little messed up. I thought it was still really beautiful, and mesmerizing, but they went on a strike, because they wanted to wash their hair. Which meant that we would have to stop shooting for 12 hours. That’s a lot when we only had five days. They formed a union against me, saying that they were ambassadors of the long-haired community. So we negotiated and in the end came up with an agreement, which was also a solution, on when exactly each one could wash her hair; another stipulation of the agreement was that every time I mention them to the press, I have to use the words beautiful and mesmerizing.”

ABOVE: Sula Fay, from her series Hair Embroideries, 2013-14

Finally, I came across, just this week, the work of a young artist, Sula Fay, currently a graduate student in sculpture at Yale, who made several years ago these simple embroideries of her own hair into vintage Victorian doilies. The works are delicate, sometimes text and othertimes drawings. I’m interested in this handwork (Fay’s) in conjunction with the handwork of the antique doilies. There’s a physicality and a delight in imperfection.

In this momentary space, we meet briefly, look, and move on. I look forward to bringing more of my thoughts and discoveries.