Backwards and Forwards to Now

Anna Atkins, 1843

Louis S. Davidson, 1940s

In two current shows in New York, Still Life, curated by Jon Feinstein, at the Camera Club, November 5 – December 19, and Surface Tension: Contemporary Photographs from the Collection, curated by Mia Fineman, at the Metropolitan Museum, I am struck by the insertion of historical work placed in proximity to contemporary images.

The title Still Life is a pun: still life as an artistic term is meant to be arrangements of things, often humble and domestic, such as Dutch 17th century painted floral studies or tabletop displays. The French term, nature morte, is even more explicit in a tacit understanding of that which is viewed being wrenched from the world of the living to a static collection of some sort. In Jon Feinstein’s show, the work is all portraiture, which in conventional terms is the antithesis of the still life: the portraits are presented as a series of masks, as formal, technological constructions. The title “Still Life” also alludes to the stilling of life, which reminds me of the panic of the portraitist in the Edgar Allan Poe story “The Oval Portrait” in which the finished portrait enacts an occult death of the model, to the horror of the artist. Or, as Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in 1859, about the stereograph, “Form is henceforth divorced from matter. In fact, matter as a visible object is of no great use any longer, except as the mould on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it.” There is also a Barthesian sadness to the title, as it alludes to the morbidity of the photograph – all we see in a photograph no longer exists as such.

Still Life includes studio work by two former members of the Camera Club, Louis S. Davidson and John Hutchins. Davidson was also a former president of the CCNY. Hutchins was also a dramatic coach who had worked with Cary Grant, Genger Rogers, Tallulah Bankhead and Lauren Bacall. He also lectured on photography through the US.

Working with models and elaborate studio lighting represented refined skill sets and photographic knowledge at its acme when these images were made in the 1940s. In hindsight, what we see now are images of great plasticity but adrift from any context beyond their surfaces. Sixty-some years does not necessarily represent much on a time line but in terms of the contexts we need to sustain meaning in photographs, it is apparent how simple and easy it is for such armature to disappear. What we are left with is the aesthetic experience of a mask, as a cipher to what had been.

A sense of future archaeological inquiry informs the selection of the contemporary work, of the portrait as a mysterious other, which can be confirmed in its formal arrangements, but otherwise evades our prying eyes.

At the Metropolitan, the show Surface Tension brings together mostly contemporary photographic artistic work which explores the “thingness” of the photograph, it’s intersections with that which it records or traces. This can include a 1:1 replica, such as a digitally stitched image of pavement (by Matthew Coolidge), physical actions upon the photographic paper by hand (Marco Breuer) or light (photograms by Adam Fuss), or light leaks which disturb a conventional image but which make it a unique thing (Wolfgang Tillmans). The show makes a case for looking at some contemporary practices, with their meta-consciousness of forms, as echoes of earlier photographic forms.

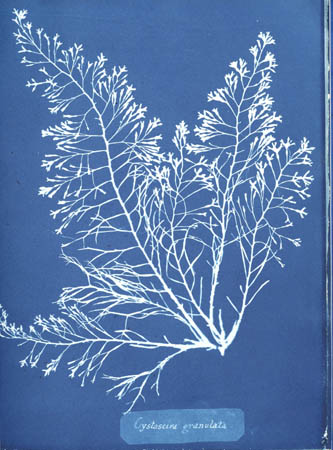

This is done with a remarkable vitrine in which there is a copy of the first photographic book, Anna Atkins’ Photographs of British Algae – Cyanotype Impressions, self-published in 1843, which predates William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, published in 1844. Atkins’ images are all photograms – the algae specimens are identified by their forms, which are seen in negative on the blue field of the treated paper. The images circulated loosely & were bound by their recipients. There are less than 20 known copies of the book. What I find so resourceful & simple to the book is that the images constitute the pages. Atkins was a botanist and amateur photographer – such an elegant solution to bookmaking.

Also in the show is a remarkable salt print facsimile of a medieval religious text, by Roger Fenton. Both Atkins & Fenton used “originals” to trace something which then be reproduced. One can’t help but see this as an aspect to a lost “golden age” (or perhaps more appropriately “silver”) of photography when it existed as a new technology and as such could be used in a remarkably fluid manner.