Milagros de la Torre – The Lost Steps

Milagros de la Torre is a lens-based artist whose work examines intimate representations of violence and its effects. She is currently featured in the publication After the Fact edited by Martha Naranjo Sandoval and organized by the ICP-Bard MFA Class of 2016. The following is an excerpt from the book.

First, I would like to thank the ICP-Bard MFA program for inviting me to be part of the uplifting conversation that normally happens within these walls. I’m especially grateful because of the subject matter we’ll be discussing here—the cross-observation and analysis of the event. Growing up in South America, I perceived and understood the notion of the event at an early age. One of my earliest memories is that of an earthquake with a 7.9 magnitude on the Richter scale. Such strength causes damage to most buildings, and causes them to partially or completely collapse.

The earthquake was the strongest impression not only of movement, but of what came later to represent the aftermath—what the event changed and what was no longer. As artists working with images, such impressions are ingrained at the back of our minds, helping us define as individual creators and producers of meaning, helping us to observe in a certain way. Such impressions often come back to haunt us and almost unwillingly become part of our own work.

Part of my upbringing was experiencing terrorism firsthand. Because of family circumstances I learned early how violence has the power to intimidate and spread fear. I grew up in Peru when the Maoist guerilla insurgent group known as Sendero Luminoso, or the Shining Path, was deploying its radical ideology and terror. Generating an internal conflict was eventful. How does one process the possibility of instant tragedy? The understanding of a beforeand-after of an incident? How can we as artists come to terms with such intense circumstances in order to interpret and translate through imagination?

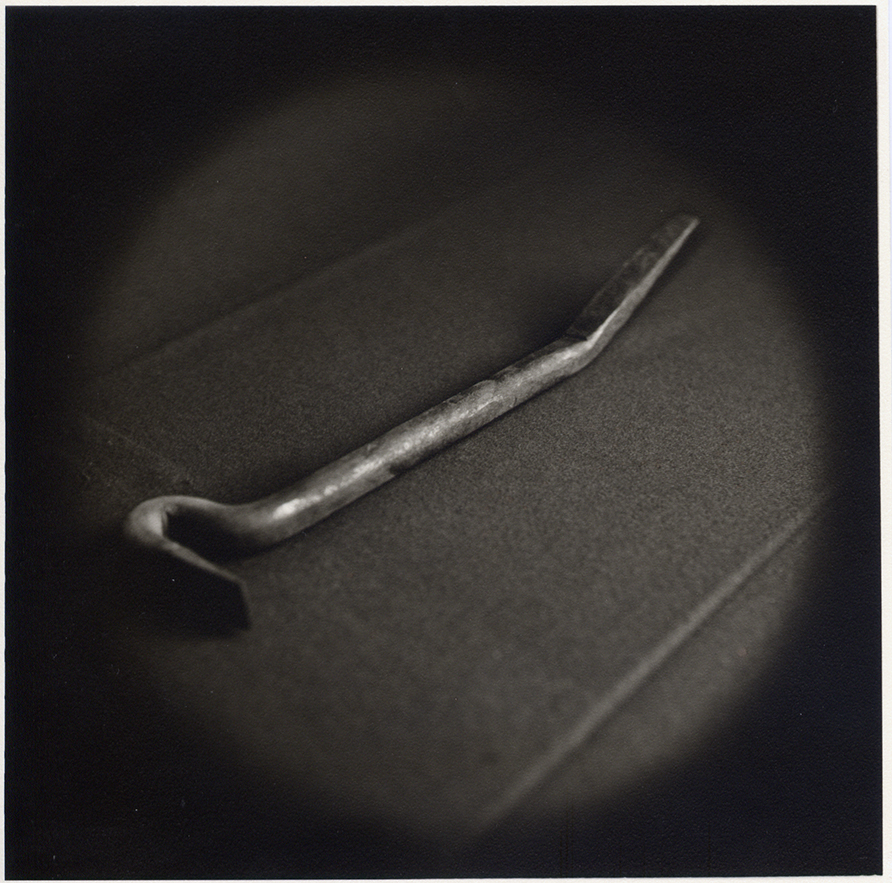

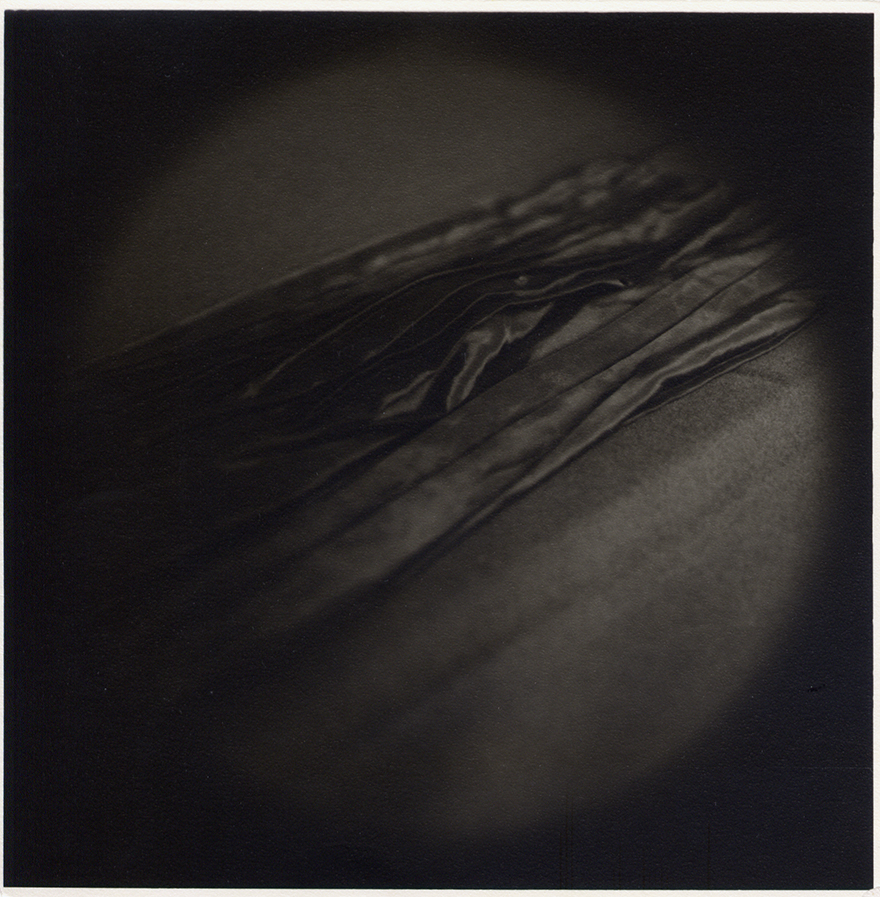

Milagros de la Torre, from the series The Lost Steps, Skirt worn by Marita Alpaca when she was thrown by her lover from the 8th floor of the Sheraton Hotel in Lima, toned gelatin silver print, 1996.

I would like to share with you the process I went through for developing a project from 1996 called The Lost Steps. The work, composed of fifteen photographs, was developed in the archives of the palace of justice in Lima, Peru. In Spanish, the archive is called Archivo de los Cuerpos del Delito. From the Latin corpus delicti, body or evidence of crime.

I was already familiar with objects being understood as evidence, but only after visiting the archives did I realize their strength as witnesses to extreme human situations. To quote Georges Didi-Huberman, “We take objects as neutral, insignificant, without consequence, which is precisely why they merit all our attention.” Images of supposedly everyday objects—a fork, a skirt—that had with a dense weight to them were presented as evidence for trials in criminal and terrorist acts, crimes of passion, and other circumstances. Their innocent origin counteracts their incriminatory testimonies.

The title, The Lost Steps, is drawn from the name given to a hallway, a long corridor of a courthouse in Lima that led from the sunlit majestic façade to the somber back of the building, where the accused waited for their hearings. It was generally believed that if one walked the lost steps hallway, one should expect imminent condemnation.

The photographs reference a process common in the nineteenth century, when the development of the optical lens was not as advanced and did not entirely cover the format of the photographic negative. The technical limitation creates a dark aura around the photographed object and makes it look as if it is floating, contextualized in a circle of light. This allows for both darkness and the light version of the object to be shown at the same time.

There is a limited depth of field, so we must concentrate our attention on a single detail in focus. The visual technique places the images in the past. Surrounding the object with a dark halo alludes to the obscure side of human nature, to the psychological intent and traces of the prosecuted. The depiction of objects is often symbolic of the still-life genre, but a singular focus of an isolated object might be more suggestive of portraiture and vulnerability, abstracting the emotionally charged objects from time or space as Susan Best noted when writing about the series.

Several factors informed the series conception. First I had to gain permission for access to the archive, which was not entirely easy. This is common when one works under military or dictatorship regimes. Fujimori was still in power, I had to prove I had been working as an artist for several years and that I was not seeking to undermine the image of Peru. Some conflicting ideas were present since the start.

I met the chief of the archive, Mr. Guzman, who had a passionate knowledge related to each criminal case and the part each object played. His memory served as a first catalyst. He had learned insider’s details since he had to collect and present the evidence from the archive, then wait in a back room until the judge asked him to bring them up front to the main courtroom. In the process he overheard privileged information from each case.

Another interesting fact is that this wasn’t an otherworldly archive where documents and records are preserved. It was a mix of different articles that were barely catalogued. It was, in a sense, the anti-archive. In a way, its sense and purpose laid within the memory of its guardian. Nonetheless, it served its function as a depository of all guilty things.

Mr. Guzman knew exactly where to find any object. If I named the case, he could find the evidence in no time. We improvised a photographic studio in the archive, then worked for several days recounting and trying to find explanations for the cases and aftermath images—where accounts are not depicted, but implied, relying solely on text to signal historical significance.

I decided to use a restrained type of text employed by law enforcement professionals under each image. This added an extra element to the work, as what might appear to be a simple fork was instead identified as a chemical test to recognize cocaine chlorhydrate made in a clandestine laboratory.

The photographs, each 16 by 16 inches, approximately the width of a human body, are large enough to fill the field of vision and small enough to draw the viewer close. I paid special attention to the characteristic of the prints, done in richly toned black-and-white fiber-based paper reminiscent of long hours spent in the dark room.

The work seems to be emblematic of our times, where there is an increasing militarization, overwhelming mechanics of violence, and a climate of insecurity where the human psyche is strongly at play. Unfortunately, they have global relevance today. Now let’s have a look at the objects of guilt.

Bullets. Belts used by psychologist Mario Poggi to strangle a rapist during police interrogation. Police identification mask of a criminal known as Loco Perochena (it was through the making of the mask that they could finally identify him). Incriminating love letter written by a prostitute to her lover. Crudely fabricated knife confiscated as evidence. Rudimentary weapon made from broken bottle and paper—one holds it a certain way to threaten a passerby.

Crowbar. Tool used to force entry. Fake police ID used by terrorist. Skirt worn by Marita Alpaca when she was thrown by her lover from the eighth floor of the Sheraton Hotel in Lima. She was found to be pregnant at the autopsy. Chemical test to identify cocaine chlorhydrate produced in a clandestine laboratory. Improvised knife made from a prison bed frame. Shirt of journalist murdered in the Uchuraccay Massacre in Ayacucho.

Thank you. I will leave it there.

After the Fact is the follow-up to the conversations sparked by the symposium After The Fact which was organized by the ICP-Bard MFA Class of 2016. The event took place December 12th, 2015 at the School of the International Center of Photography. The symposium explored how we process personal and political information, how we view and contextualize art, and how both fact and fiction inform our everyday realities and our senses of self. It examined the place and potential of The Event—natural disasters, encounters with works of art, acts of political resistance, the genesis of authentic love— all points of no return. What happens when we feel, live, and experience the intensities that emerge, as if out of nowhere, as miraculous forces? How do we relate to contingencies, which change the way we perceive ourselves and engage in our world?