Photo Book: “All the Queens Men” by Katie Murray

Katie Murray is a Queens native and photographer / video artist / photo professor that I had the wonderful experience of meeting over cocktails at Noorman’s Kil in Williamsburg earlier this summer. Katie and I are both publishing our first books this month with Daylight Books and taking part in a panel discussion this Saturday night at 6:00pm at Photoville in DUMBO Brooklyn. Our talk, moderated by Michael Itkoff and Taj Forer of Daylight Books, is titled “Family Matters” and will also feature Henry Jacobson and Sarah Christianson along with Katie and myself to discuss our new books and the different ways we all tackled themes of family and connection to the land in our work. With her new book titled “All the Queens Men,” Katie Murray explores her Queens, NY neighborhood as a paradise lost in the decade following September 11th as seen through the eyes of the men who surround her and the streets on which they live.

SM: “All the Queens Men” is such a great title for a book about men and masculinity set in Queens, NY. And I love how it also references your role as a woman who holds some authority over these men, in this case as the person taking their portrait. How did that title come about and what made you decide to run the title only on the book cover with no image?

KM: From the onset of this project I knew I wanted to play off of the word Queens because I think it’s such an interesting word as it calls to mind that which is majestic or mythological. It is also a powerful word as it relates to women, and I always thought it was interesting to be a woman photographing men in a place named Queens. I began to think about these men and this place as a mythological kingdom albeit a fictitious one, but this idea altered the way in which I approached the subject matter and allowed me to play with fiction and non fiction and be free to make work that existed somewhere between the two. Additionally, All The Queens Men is a play on a line from the nursery rhyme Humpty Dumpty. A line, which I think is filled with pathos and hints at one of the themes of the book.

In terms of the all text cover, it came about because after numerous tries, no one image from the book actually worked with the title, but the title worked by itself as a mysterious entrée into this world. There have been many all text cover photo books but the most well known or referential as it relates to my work is Walker Evans’ American Photographs-and with this also in mind I went with the all text cover.

SM: In the book’s beautiful essay by Maria Antonella Pelizzari, she quotes you as describing the landscape of Queens as “both tragic and beautiful” and how that reflects the duality in the men you photograph. The way you photograph these men is straightforward and shows their flaws but there’s a nurturing quality like you love them not in spite of those flaws but because of them. How much of that would you attribute to being a mother of boys? How much of it is being a Queens native yourself in feeling this kinship with your subjects?

KM: I would say that the nurturing aspect you are picking up on has more to do with being a Queens native than a mother of boys. I am by no means photographing the other.

My children were born in 2006 and 2009 well after the work was already in progress. That being said though, having children and becoming a parent did make me aware of the shifting roles that take place when one transitions from being a child to having a child, and this is an idea that is present in the book as it relates to the men.

SM: These photographs span from 1999 to 2013. Obviously, the most significant cultural event that happened in New York during that time was September 11th. Pelizzari goes on in her essay to speak about 9/11 and how that monumental trauma and loss acts as the backdrop to the story of this place and the men that inhabit it. There was a photograph from 9/11 that I saw on your website. Am I right that at a certain stage of the project this image was included in your edit? What made you edit it out of the book?

KM: The picture you reference was made on September 11 2001, and while it was never in any of the many edits I wrestled with, it was a consideration. In the end I decided that it was too referential; it was a one to one relationship, one that swayed the ambiguous narrative in a direction that was inauthentic. The book is not about 9/11 per se but instead is a reflection on the residue of that traumatic event. I felt it was more powerful to speak about that event in symbolic terms rather than be so obvious, and thus the picture was edited out.

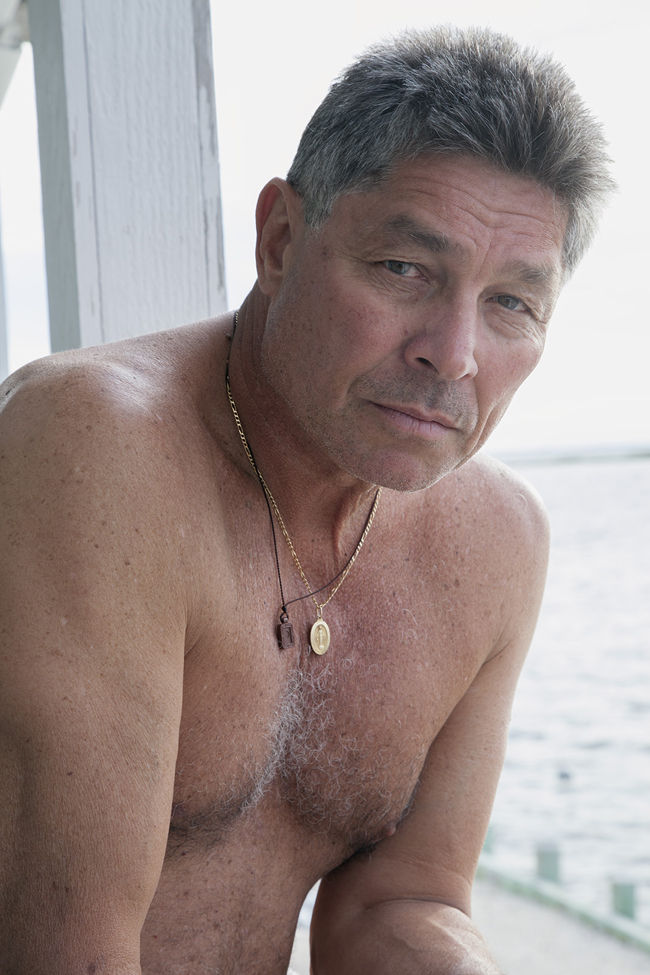

SM: Daniel is the subject of many of the photographs and acts almost as a protagonist to the series. What is your relation to him and what were your experiences photographing him? Did it change over the course of the project?

KM: I think the book has more than one protagonist, but if the book has a main protagonist than it would be Daniel. He is the father figure, and is also my father. Making portraits of people you are so connected to and intimate with is always challenging for countless reasons, but perhaps he appears so often in the book because it is always a pleasant experience photographing him. He has never refused to let me make a picture of him; he is always a willing participant and is difficult to work with only because I have to scold him to be serious. Portraits of my father/Daniel are made in-between fits of laughter on both our parts, and that has been consistent throughout.

SM: Towards the end of the book, there’s a spread I want to talk about. On the left is a photograph of an uprooted tree on a suburban street. Because of the perspective of the image, the tree is almost as tall as the house and there is a dark shadow in the middle of the tree that creates the appearance of a cave. Accompanying this image is a photograph on the right titled “11 Boys, Queens, New York 2003” that depicts a group of teenage boys standing in a circle on gravel, many shirtless, with one blindfolded in the center and another boy behind swinging something toward him in what looks like some kind of hazing ritual. The overgrown grass and shrubs surrounding them give a “Lord of the Flies” vibe to the proceedings. The fallen tree and the bullying amplify a feeling I get throughout the book of innocence lost. What is the story behind these images and what was your thought process in pairing them together?

KM: The ways in which images relate to each other and inform each other is one of the amazing things about being a photographer. Often times I would be making a picture while thinking about how it would relate to a previous image and how you can build upon ideas in multiple pictures. The entire book was edited with this thought in mind. So that you would have a book of images that tell a story, and then with more time spent, another deeper story would be revealed. So yes, one of the themes of the book is innocence lost. The pairing you describe is an uprooted tree and a fictitious rite of passage. In this pairing an act of violence has been experienced or is being experienced; so at its base level it’s about violence, but it’s also about not being grounded or rooted and the attempt to find meaning in a ritual that may or may not grant you a sense of belonging.

SM: We are both publishing books with Daylight in the fall. How did you come about working with them?

KM: I was fortunate enough to have applied to a book-publishing grant when one of the publishers at Daylight (Taj Forer) was a judge. As a result, Daylight reached out to me with interest in publishing my book, and the rest as they say is history.

SM: What was the best advice you received in preparing to publish your book? What advice would you give to another artist who was embarking on their first publishing experience?

KM: The best advice I received was to make the book that I wanted to make, and to keep in mind that it will not be the only book I publish. I’m not sure if the second part of that will be true, but it was invaluable because it allowed for me to be free to take risks and to not be safe. (ie the text cover)It’s important to know what you want from the onset, to ensure that you’ll end up with the book that’s in your head.

SM: What are you working on these days?

KM: I’ve just completed a video piece entitled “Gazelle” that reflects upon the struggles one faces as an artist, mother, and wife. It is the first time that I appear in my work, and it’s also the first piece I’ve made that is humorous. “Gazelle” will be shown in October at The Photographer’s Gallery in London in a show entitled Home Truths: Motherhood and Photography curated by Susan Bright.

SM: You teach photography at Hunter, SVA, and Sarah Lawrence. What is your philosophy on teaching photography and what words of wisdom do you try to impart on your students?

KM: Teaching photography is challenging especially since it is a common practice amongst my students in the sense that they are all using pictures in their daily lives with Facebook, Instagram, and the like, so my approach is to try to get them to realize the potential of the medium as a meaningful tool.

SM: As we say goodbye to summer and enter into fall, what’s your idea of a perfect late summer day?

KM: Enjoying a lazy morning with my husband and boys, and a late afternoon trip to Rockaway Beach where we hang out until the sun sets.

For more from Katie Murray and to pre-order her book “All the Queens Men,” please visit her website: http://katiemurray.com/