Photo Book: “Road Ends in Water” by Eliot Dudik

I first came across Eliot Dudik’s incredible self-published photo book Road Ends in Water at Carte Blanche Gallery in San Francisco where both our books were featured in a show curated by Larissa Leclair of the Indie Photobook Library and Darius Himes of Radius Books. And thanks to a suggestion by Jennifer Schwartz of Jennifer Schwartz Gallery, Crusade for Art, and Flash Powder Projects fame, we were recently reconnected to discuss our adventures in the world of first-time book publishing.

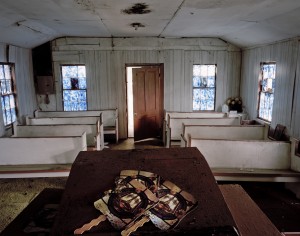

Having grown up on the outskirts of suburban Texas where the strip malls meet the farmlands and having spent my entire adult life living in New York City and Brooklyn, I tend to gravitate towards work dealing with the American landscape. In this body of work, Eliot Dudik chronicles the spirit of the South Carolina Lowcountry: its swamps and dirt roads, its weathered porches and ramshackle churches, and the people that are as much a part of this landscape as the giant oak trees that tower over it all. There is an ebb and flow to the sequence of images that rolls along like currents in the deep waters it portrays. This book feels like a baptism. I spoke with Eliot about the two years he spent working on this project while traveling from Charleston to Savannah, Georgia where he was a graduate student at the Savannah College of Art and Design and his experiences turning this project into a beautiful book.

SM: First of all, it was such a pleasure sitting alone in our apartment today for about an hour slowly going through the book and then re-reading and re-looking a couple times. It’s a really great meditation on a certain place and time and on large format photography as a medium. Large format photography is a long tradition that is becoming increasingly difficult for photographers of our generation to afford or even have access to processing. To that end, I’m going to kind of get ahead of myself and ask: how much does the slow, somewhat antiquated nature of large format photography factor into your process documenting a place steeped in its own deep traditions and slower pace? Was that something you thought about during the making of the work?

ED: The use of a view camera factors into my work quite extensively. It is the effects of the view camera on the land, my subjects, and myself that dictates my using this type of camera. Above all else, I enjoy the slow, contemplative and methodical steps associated with camera. It helps me to remain within the landscape. I see it as penetrating into a bubble, whereas I sometimes have difficulty piercing the surface tension with other formats. When making portraits, I enjoy the interaction between the subject and the view camera. They often have a look of pride and confidence in their expression and the way they carry themselves that is sometimes lost when looking down the barrel of an SLR.

SM: Road Ends in Water is such a great title. I know it comes from the road sign you photographed that appears in the beginning of the book. Did you take that photo knowing it would become the title or was that a decision you made once you were in the editing process?

ED: I took the photo for its symbolism and because I thought the sign was funny. It didn’t become the title of the series until the final editing stages. A professor and mentor, Jenny Kulah, suggested it as a title, and it made perfect sense.

SM: What I love about the title is the symbolism of “road” and “water” that appear throughout the book. Both are metaphors for the cyclical nature of life and death. All of the titles of the images refer to their location as being either a river or a road. There’s a definite sense of a journey or being in between things. It feels to me that this body of work operates on many levels: it is a documentary of a little seen pocket of America that is disappearing in the wake of government projects and economics, it is a metaphor for your life being in a somewhat transitional stage being a grad student during the project’s making and this new focus of your life in photography, and it has far broader themes of death and lost traditions. That’s where my head is at, but I’d love to hear your thoughts.

ED: You pretty much hit upon everything. The landscape in this region of the country is renewed, flushed, and emptied by a multitude of rivers and tributaries heading toward the ocean. The rivers bring folks together here as much as the roads do. Generations of families have persevered here, living off of the land and rivers.

SM: Your portraits have a lived-in quality. Yet, having grown up in rural Pennsylvania, you are an outsider to this community. How did you approach the subjects of your photographs? “Tom & Tommy, Prices Bridge Road” and “Rob & Ricky, Near Martins Landing” in particular feel like people you know or were mid-conversation with when you set up your camera.

ED: I had lived in the Lowcountry for about six years at the point that I made these images. The landscape and the way of life had initially drawn me to the South. I felt very comfortable with it, yet at the same time, in a constant state of awe. Focusing on this series, I allowed myself the time and solitary peace to traverse the roads and waterways throughout this region for hours on end. I often met folks by happenstance and we would often converse for long periods of time. In the example of Tom and Tommy, I had passed Tom’s house three or four times very slowly, taking in the landscape, and eventually he stopped me and asked if he could help. I explained who I was and what I was doing, and he invited me in to see his framed photo within a newspaper clipping about a local barbeque chicken cook-off. We talked for a while with a couple of his friends, including Tommy, and they asked me to take a photo of them with their barbeque cooker and confederate flags, which I did. We later made the image down on the dock that is in the book.

Rob and Ricky came flying into a river landing in their pick-up truck, spitting gravel everywhere, and came to a halt about 15 yards from where I was set up to make a photograph. They jumped out of the truck and proceeded directly into the swamp near by. I continued about my business, and soon looked up to see Ricky calling to me to let me know that they were going to fire off some guns. I waved to him, packed up my things, and headed into the swamp. They were shooting at tree stumps. We talked for a little while, and they agreed to make the photo that’s in the book.

I sometimes had longer relationships with some of the folks I photographed, seeing them on different occasions as I drove through the area.

SM: The book contains 3 poems, one of which was written by your father. What is your relation to the other 2 authors and why did you decide to include these throughout the book?

ED: Brianna Stello is a friend of mine from Charleston, South Carolina, who is also a photographer. I had read some of her poetry years prior to making the book, and when the time came, I sent her some of my images and asked her if she would be interested in writing something to pair with them.

Dr. E. Moore Quinn wrote an essay that is included in the book. She was one of my Anthropology professors when I was an undergraduate, and continues to be a great friend. She had shared my work with her friend, poet Jerri Chaplin, and Jerri wrote a piece to accompany my photographs as well.

I found the writings to help expand the reading of the photographs.

SM: I definitely see the Alec Soth and Joel Sternfeld influences in your work. They are big influences of mine as well. What other artists were you looking at in relation to this specific body of work? The South is so steeped in incredible writers and musicians- did that offer inspiration?

ED: William Christenberry, Richard Misrach, and Stephen Shore were a few other photographers I was interested in at the time, and still am. I would have to say photobooks were my biggest inspiration during the time I was making this work. All sorts of photobooks, I just gobble them up. I am a big music fan as well, and my taste in music is much like my taste in photobooks, it runs the gamut. Although it would have been a great time to draw inspiration from music while in the car, traveling through the landscape, but I chose to instead mostly listen to NPR and chew sunflower seeds.

SM: Let’s talk about photo book publishing. Roads Ends in Water is self-published, right? And what influenced the decision to make a book? Did you always envision this project as a book?

ED: Yes, it is self-published. I find photobooks to provide a viewing experience much different from a gallery setting. Often a photobook is enjoyed in a quiet, private, and comfortable space, giving the reader the capacity to fully engage with the work. It also lends to the narrative nicely, which can help endow the work with new meaning. I did always envision this work as a book, even before I knew how the work was going to turn out. The self-publishing process was something I was researching during the entire time I was photographing the area. Not only does the photobook provide a more intimate viewing experience, but it also helps me to get the work out to a larger audience than I can solely through exhibition.

SM: Is Saga Publishing your own brand, like Alec Soth’s Little Brown Mushroom?

ED: Yes, Saga Publishing is my own brand. I came up with it at about two in the morning when I was trying to finish a mock-up in time to take to a photo conference. It seemed fitting at the time.

SM: How did you raise the funds to publish 1000 copies?

ED: My Grandmother helped me to fund the printing of the book. This is only one of many reasons the book is dedicated to her. She is a great woman.

SM: In our past conversations, we talked a bit about the inevitable mishaps that seem to occur with every printing experience. The advice is always to be on-press, but for me it was so expensive to make the book at all that the additional cost to travel to press wasn’t affordable. What was your experience with printing with a press in Iceland?

ED: I wanted to travel to Iceland to see the book coming off the press more than anything. I tried to come up with a way I could make it over there, but alas, I was in my last quarter of graduate school, and had several things to pull together in addition to the book. Oddi, the Icelandic printing company I worked with, was terrific. They sent me a physical proof to study, and after that was signed off on, they then sent me a digital proof just to make sure everything was laid out and ordered the way it was supposed to be. Typically, they would send two physical proofs, but because of my time restraints, they sent one physical, and one digital. They sent me some advanced copies in time for my book release and thesis exhibition, and the rest showed up on a pallet a few weeks later. They have a representative here in the States that helps to translate the job to the printing house in Iceland. Everything went smoothly.

SM: We’re both adjunct photo professors. I remember being an undergrad photo students and always wishing there was more real-world advice for how to get your foot in the door in any area of the photo world. It’s the same thing I hear from my students now, which I make a point of devoting at least a whole class to answering those kinds of questions. What is the best advice you give your students?

ED: I treat all of my students as artists, and hold them to the same expectations they will encounter after graduating. I discuss marketing strategies with them in every class. I encourage, and sometimes require submissions to publications, calls for entry, juried and solo exhibitions, internships and apprenticeships. Most importantly, in my opinion, I encourage them to, and mentor them through attending events and conferences like the Society for Photographic Education. I find these kinds of events to be invaluable for emerging artists for a number of reasons, but especially for the networking possibilities. I think we had 12 students or so attend the SPE conference in Chicago last year, and I think they would agree that the experience was remarkable.

SM: What are you working on now and do you see it as a continuation of or departure from the themes or methods of working that you established for yourself in Road Ends in Water?

ED: I recently began working on a new project that explores the American Civil War, especially as it exists in our consciousness today. Fortunately, this work is coinciding with the 150th anniversary of the American Civil War. There are a few different components to this project so far. I am creating landscapes of battlefields, both well known and obscure, with an 8×20 inch view camera. However, instead of using black and white film within this camera, I am using two sheets of color 8×10 inch film. This creates a separation in the image, which I am quite fond of, and lends to all sorts of symbolism. I am also traveling to reenactments to capture the essence of war among some of these battlefields. Additionally, I have begun the portrait component of this project this past weekend at the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. I am very excited about these. They are quite unique in their construction, and I think they will lend nicely toward my interests in the cyclical nature of repeatedly reproducing such a bloody war. I am also collecting sounds as I move through these landscapes and episodes that will permeate the photographs.

I would think this new project is somewhat of a departure from Road Ends in Water in technique and construction, but in many ways its also a continuation. I think it retains the sense of a journey, an investigation into life, death, conflict, and varying perspectives on an important subject. Although the equipment I am currently using to interact with the landscape is different, I am still working by the same principals: see, feel, think, create.

SM: And lastly, what’s your ideal summer day?

ED: Ideally: Air conditioning, coffee, images, music, ham and cheese on rye, loved one/s, cards or darts.

To purchase a copy of “Road Ends in Water” please visit http://eliotdudik.com/ and click on “Book.”