Photography and The Black Panther Party

Sadie Barnette’s Do Not Destroy solo show opened last week at Baxter St to a roaring reception. It’s not every day that you get to see a gallery show that features the classified FBI documents of an ex-Black Panther Party member. That Panther is Rodney Barnette, who founded the Compton, California, chapter of the Black Panther Party of Self Defense in 1968. The centerpiece of Barnette’s show is undoubtedly the wall filled with copies of her father’s surveillance files, embellished in the artist’s signature “graffiti” and faux jewel treatment.

Barnette’s show features minimal photography. Opposite the wall of FBI files stands two seemingly life-sized portraits of a young Rodney Barnette that his daughter/the artist has rephotographed. On the left we see him smiling in his US military uniform. In opposition, to the right is Barnette captured in harsh flash donning a black beret, t-shirt and leather jacket; his dark shadow looms large behind him as he looks off camera. This photograph of Rodney is untitled, and yet we need no explanation that this is a changed man, reincarnated as a BPP member.

Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Huey’s Apartment, Oakland, California, 1971

In the juxtaposition of these two portraits, the viewer contends with the use of photography as a witness to Rodney’s shifting identities and ultimately the medium’s political power. Without going into the internal politics and covert government action that caused the party to disband, I’d like to briefly discuss what art critic John Berger considered to be “the crucial role of photography in ideological struggle” and the Black Panther Party’s strategic use of photography (and posing) in crafting their own brand of Black anti-fascism.

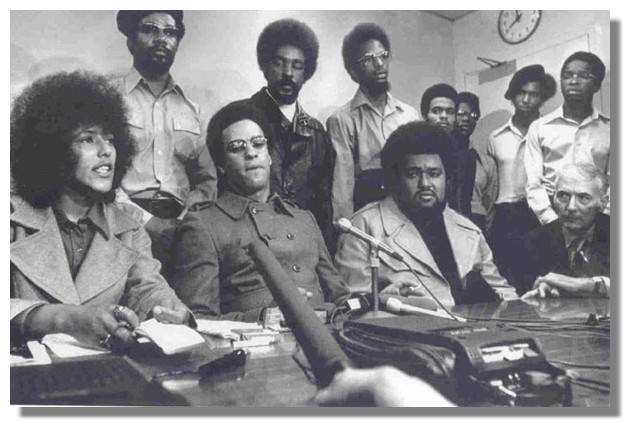

Elaine Brown (bottom left) and to her side Huey P. Newton leading the Black Panthers at a press conference in San Francisco. (October 1971)

Many B&W photographs exist of the high profile BPP leaders. Both male and female members are pictured in socio-political context: raising fists, encouraging crowds, marching in demonstrations, standing in formation, working at their headquarters, being interviewed by and addressing the press, conversing critically with each other, meeting other political leaders, performing community service or even just relaxing at home.

Wanted by the FBI, Interstate Flight – Murder, Kidnaping, Angela Yvonne Davis. Gift of Brian Wallis, 2010. Courtesy of the International Center of Photography.

Then we see the isolated figure: numerous solo portraits of Bobby Seale, Stokely Carmichael, Huey Newton, Angela Davis, Kathleen and Eldridge Cleaver. This image of the lone revolutionary becomes ubiquitous just a few years earlier with Cuba’s Che Guevara and the Black Panthers utilize their portraits on paraphernalia like flyers, buttons, posters, t-shirts, publications. Sometimes these solo portraits were used to vilify the Panthers, like in the wanted poster below of Angela Davis. (Side note: you can view this poster in person at the ICP Collections at Mana Contemporary in NJ. It’s quite an amazing experience!)

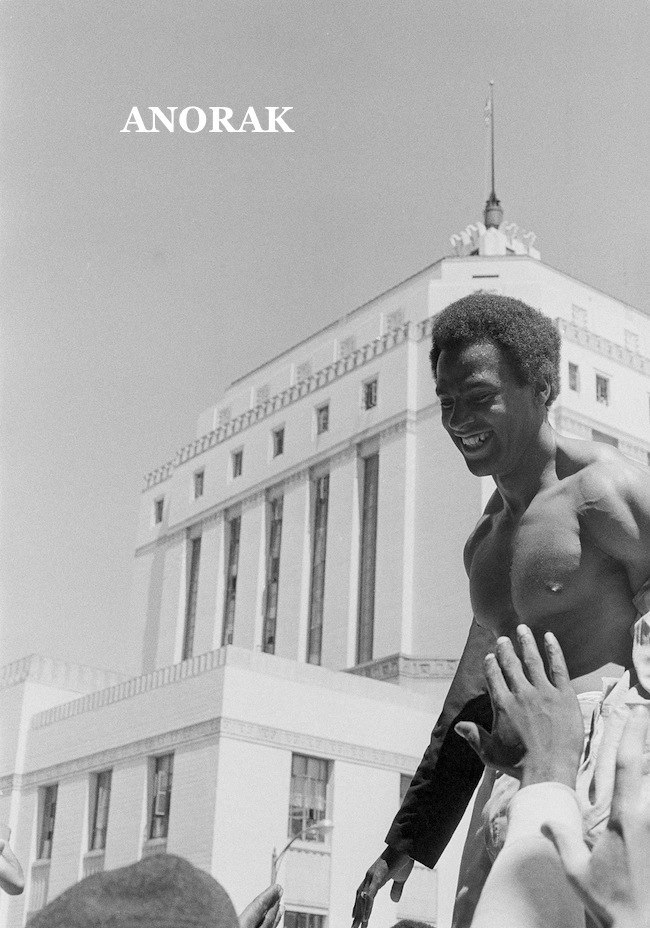

Stripped to the waist in the afternoon sun, Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panthers shakes hands with followers and friends who greeted him as he walked out of the Alameda County Courthouse in Oakland, Calif., Aug. 6, 1970.

The Black Panther Party’s visual message also conveyed their unique style and sex appeal, both aspects of the party’s identity that no doubt helped with recruitment efforts. Jet black leather jackets, Ray Bans, berets, perfectly coiffed afros merged effortlessly with the sleek profiles of .357 Magnums, 12-gauge shotguns, and .45-caliber pistols to create an impressionable representation of Black power.

Portrait of Kathleen Neal Cleaver by Howard Bingham.

Both Kathleen Cleaver (BPP communications secretary and wife of Eldridge) and co-founder Huey Newton became the party’s default sex symbols. Newton was pictured exhibiting his bare-chested, muscle-toned physique both at home and when he was freed from prison in 1970. Bingham’s images of Cleaver portray her as a thing of beauty though she may not have intended this to be her role. Yet Cleaver did play with fashion by often sporting a large afro, hoop earrings and the radical above-the-knee length skirt style thus creating a new revolutionary aesthetic in clothing for (Black) American women. The Black Panther style was even appropriated in advertising as seen in this vintage ad for Newport cigarettes.

A Black Panther feeds his son at the “Free Huey” rally in Oakland, California. February 17, 1968.

Not only did the Black Panther Party provide political power for many Black Americans, but they also affirmed the notion of family. This familial bond was forged mainly through offering life-sustaining services like free breakfast programs and community schools operated in cities like Oakland, CA. So not only do we see Panthers providing children with nutrition and education, but we also see children in attendance at rallies and marches. Of course, the most famous BPP child was Tupac Shakur, son of party member Afeni Shakur.

Knowing that the photographic image is only as empathetic as the photographer behind the lens, the BPP leaders were strategic in appointing Stephen Shames as the party’s official photographer. In another move to control their image, Muhammad Ali’s personal photographer Howard Bingham was contracted for six months to shoot a 1968 cover story for LIFE magazine upon the insistence of party leader Eldridge Cleaver.

British Black Panthers take to the streets of London. Photograph by Neil Kenlock.

Despite the negative reports and judgements about who they were, the Black Panther Party members were in full control of their own image as surely they knew their supporters and haters around the world were watching. The BPP’s strong message spread overseas in areas where other Black communities were struggling for their own civil rights, inspiring regional groups like the British Black Panthers – see the work of Neil Kenlock. In this time post-US election where many are preparing for struggle once again, we are fortunate to be able to reflect on these images.

For additional viewing, I’ve created a Black Panther Party Photography board on Pinterest. Also, the Smithsonian Institute has an excellent BPP archive of black & white, documentary photographs from the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Sadie Barnette’s Do Not Destroy, curated by Alexandra Giniger, is on view at Baxter St now through February 18, 2017.

Qiana Mestrich is a photographer, writer, digital marketer and mother from Brooklyn, NY. She is the founder of Dodge & Burn: Decolonizing Photography History, a blog that seeks to establish a more inclusive history of photography, highlighting contributions to the medium by and about people of underrepresented cultures. Read her other guest posts on the Baxter St blog: The Black Female Self in Landscape, Forthcoming Photbooks by African American and Black African Photographers and In Memoriam: John Berger and Uses of Photography Quotes.