Photography and Violence 3: Carlos Aguirre and the Mexican Landscape

It was not only its escalation and its geographical expansion that set apart the violence experienced throughout the so-called “war against drug trafficking” in Mexico. It was also the brutality of the executions; its expressive level of cruelty, which is impossible to forget. The violence exercised by the narco-gangs or the narco-machine as Rossanna Reguillo calls it, is determined to dissolve the singularity of human beings by turning them into suffering bodies, sometimes fragmented –heads, torsos, legs, arms. These bodies, exposing their own vulnerability, are a mirror of Mexico’s inoperative political and judiciary system, one that allows a contagious spread of criminality and leaves thousands of crimes, related and unrelated to drug trafficking, unresolved. For Felipe Calderón’s office –which declared war against the drug cartels in 2006 with an over-confident discourse that assured that “we are not going to war if we are not sure that we are going to win” –the dead became a negative image. And because we are not talking about one or two, but more than 120,000 violent murders in a six-year term, the constant representation of the dead became evidence of an explosive national crisis.

Contrary to President Calderon’s wishes –who urged the media to “give violence its proper dimension,” and criticized the press for “amplifying” the problem of Mexico’s violence– Mexican artist Carlos Aguirre (Acapulco, 1948) started collecting violent imagery from local “sensationalist” tabloids of the state of Morelos. Aguirre belongs to a tradition of artistic activism similar to that of its Latin American counterparts who criticized the military dictatorships and dirty wars of the 1970s and 1980s. As part of a generation that responded to the political and social unrest that emerged in Mexico in 1968, he has positioned himself as an artist who emphasizes the tensions between economic, social and political realities.

His work Paisaje mexicano (Mexican Landscape), which is exhibited permanently at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana in Mexico City, is a large-scale mural (3 x 12 meters) that consists of the recompilation of approximately 1,400 nicknames of drug dealers and hundreds of newspaper clippings of photographs of violent deaths. These nicknames, arranged chaotically, one on top of the other in different opacities of black, create, from a distance, an indecipherable mural. When one gets closer, the words become clear: one can recognize famous capos, such as “El Chapo” and “El Barbas,” printed in large bold letters, as well as lesser-known nicknames, such as “El Harry” or “El Koreano,” in smaller fonts.

Carlos Aguirre. Paisaje mexicano (Mexican Landscape), 3 x 12 mt., 2010. Vinyl and newspaper clippings.

Aguirre’s overwhelming universe of drug-dealers can be seen as a powerful interpretation of the narco’s strategic multiplication throughout Mexico’s geography. According to Reguillo, the narco-machine’s power relies on its unfathomable presence, on the fact that it is always strategically de-localizing itself. Aguirre’s Mexican Landscape deliberately follows a traditional composition of a landscape, in which a horizontal line is used to enhance an open view of the scenery, giving a sensation of vastness and continuity. This horizon is constructed by pasting hundreds of color photographs of violent deaths, following one editorial criteria: selecting “the most violent images” found, since, according to the artist, “these images respond to the cruelty that has escalated.”

Carlos Aguirre. Paisaje mexicano (Mexican Landscape), 3 x 12 mt., 2010. Vinyl and newspaper clippings. (Side view)

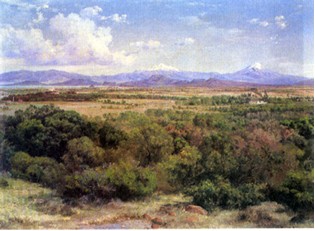

Aguirre’s usage of sensationalist photographs is his own way of depicting his contemporary abject version of a Mexican landscape, opposing the celebratory and colorful landscapes of the Mexican valley by famous Mexican landscape painters, like José María Velasco (1840 –1912) and Gerardo Murillo (Dr. Atl) (1875 –1964), with the latter turning Mexican geography into a positive symbol of post-revolutionary national identity, through the use of lively blue skies, rich foliage and mighty volcanoes.

Conversely and quite unexpectedly, Mexican Landscape also reminds me of Rothko’s No.5/No 22 (1949). More precisely, what it recalls is Anna Chave’s symbolic interpretation of the canvas. Her controversial take suggests that the horizontal framing derives from earlier depictions of dead figures lying horizontally. If Chave was right and Rothko’s pictorial segments have symbolic references to entombments, in the case of Aguirre the reference is more than just symbolic: it is obvious. Moreover, in Aguirre’s horizontal placement of the images of the dead a far more wretched image is implicit: that of a massive grave.

Mark Rothko, No. 5/No. 22, oil on canvas, 1950. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York