Photography and Violence 6: Ilán Lieberman’s Lost Child

According to Mexico’s Senate, between three or four children disappear every hour in the country due to the following causes: 67%, illegal abduction of parents in conflict with each other; 9.3%, voluntary absence (victims leave home because of domestic violence or sexual abuse from parents or other members of the family); 9.3%, theft; 2.3%, minor gets lost because of parents neglect; 1.2%, kidnap. The remaining 10.9% stands for children that went missing due to an “undetermined cause,” which means that one day they simply “disappear.” [1]

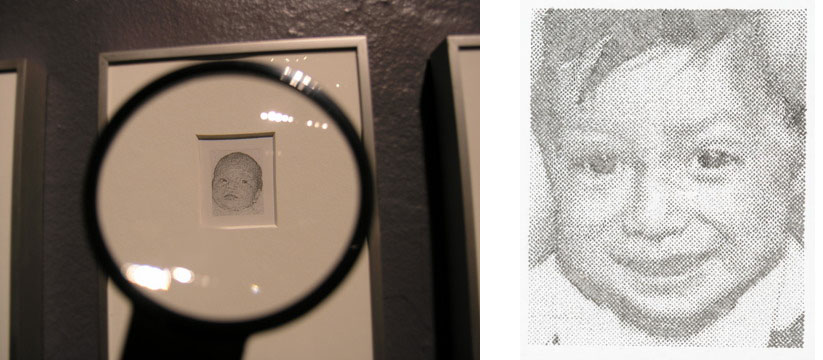

Ilán Lieberman, Lost Child, exhibition view. Museum of Modern Art. Paris.

Lost Child (2005-2009) by Mexican artist Ilán Lieberman (b. Mexico City, 1969), is a series composed of one hundred small-scale portraits of missing children in Mexico. These portraits, measuring approximately 1 x 0.82 inch each, are meticulous hand-made reproductions of photographs originally found in the section “Far Away From Home” of Metro, a Mexico City local newspaper. Each of the photographs is published with basic information of the child –age, height, distinguishing characteristics, and the place and date of his or her disappearance– that could potentially help to recognize him or her; information that Lieberman includes as labels of each work. For example, one of the labels of the one hundred children in Lost Child reads:

Nuria Alejandra Albarrán García

Age: 13 years

Height: 4′ 11″

Distinguishing characteristics: Scar on right forearm.

Place and date of disappearance: Unidad Bellavista Neighborhood, Borough of Iztapalapa, Mexico City, June 13 2005

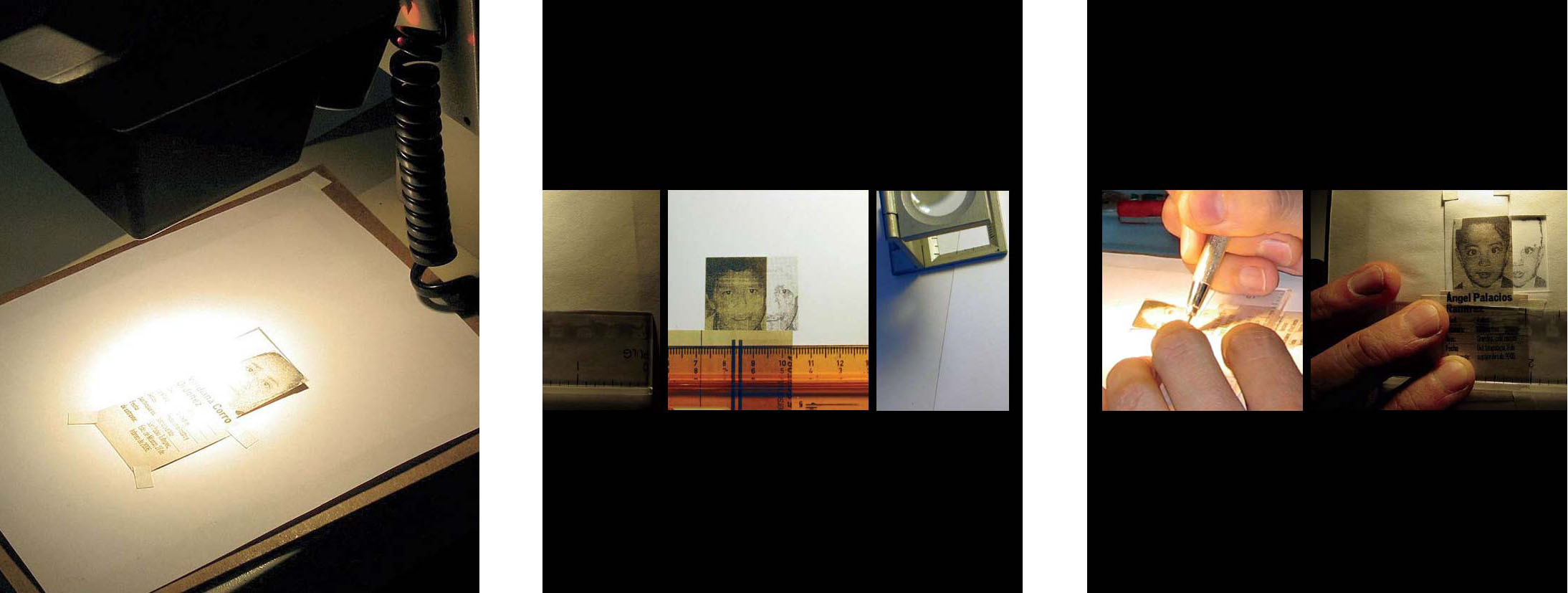

Lieberman’s clippings of missing children of section “Far Away From Home” (Lejos de casa)

from Metro newspaper. Credit: Ilán Lieberman.

Each one of Lieberman’s one hundred drawings of missing children is a hand-made replica of a low-resolution photograph found in a newspaper. Instead of just doing a photocopy of a newspaper, Lieberman selects a manual format, using a microscope to capture every detail. It is noteworthy that each of these drawings took him between seven to fourteen days to complete. When Lieberman exhibits the series Lost Child he places magnifier glasses, so the viewer can get closer to the process he undertook in carefully drawing each face. With the magnifier glass one gets a chance to examine these drawings closely and see the hand-made dots that compose each work. Lieberman’s drawings focus on the particularity of each child’s facial features. This work has a strategy: individualizing each disappeared child, deifying the vagueness of statistics in a desensitized society. Lieberman says that “we pass every day by stoplights and see children begging or homeless, and they already become part of the landscape. That’s something you have to get used to when you live in Mexico.”[2]

Lost Child. Credit: Ilán Lieberman.

By choosing to do these portraits hand-made, Lieberman is relying in the permanence of the artwork, a recurrent concept that has been used by some scholars to discuss his work. According to Mexican art critic María Minera, permanence is the most important factor of the series; she argues that “That in the careful strokes goes the possibility for these photographs not to vanish in less time that one changes a page [of the newspaper]”[3] In the same vein, critic and curator Michel Blancsubé has expressed: “The remarkable thing about this artist’s approach is the way the transition from offset to pencil on paper, from printed page to work of art, brings permanence to something initially utterly lacking in it.”[4] What these critics are suggesting is not that a newspaper, as a medium, is impermanent (a newspaper, if taken good care of, could last for a very long time) but that, given its periodicity, it is usually inspected in a hurry, sometimes without really being read, and thrown away day after day.

Lieberman’s hand-made process/drawing technique. Courtesy of Ilán Lieberman.

One can find a reaction towards transience or ephemerality in Lost Child, since it criticizes the way in which the issue of the missing children is perceived in a mechanically reproduced medium, where this particular issue is consumed like any other subject-matter, without the proper attention it deserves.

Detail of Ilán Lieberman’s Lost Child exhibition in Mexico City.

Credit: Deborah Bonello / Los Angeles Times.

For more on Lost Child visit this link:

http://www.ilanlieberman.com/sg/lostchild/lost.html

[1] Daniel Blancas Madrigal, “Cada hora desaparecen en México de 3 a 4 niños,” Crónica, February 11, 2013. http://www.cronica.com.mx/notas/2012/677990.html [accessed November 1, 2013].

[2] “Pasamos todos los días por los semáforos y vemos niños o indigentes que piden limosna, y ya se nos hace parte del paisaje. Eso es algo a lo que uno tiene que acostumbrarse al vivir en México”, says Lieberman. Sergio R. Blanco, “Los niños perdidos de Lieberman,” Reforma, May 24, 2009.

[3] “Que en sus trazos minuciosos va la posibilidad de que esas fotografías no se desvanezcan en menos de lo que se cambia la página [del periódico].” María Minera, “Fotografías hechas a mano,” Letras Libres 123 (March 2009): 74.

[4] Michel Blancsubé, “Confusion Will Be My Epitaph,” in Esquiador en el fondo de un pozo, ed. Michel Blancsubé (Ecatepec de Morelos, Estado de México: Colección Jumex 2006), 269.