Photography and Violence 7: Archival Impulse

Rosângela Rennó, Río-Montevideo (2011)

Brazilian artist and photographer Rosângela Rennó (b. Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 1962) explores in a systematic way historical objects with the aim of contextualizing them in its time and place, working obsessively since the 1980s with visual archives as her “raw material.” In 2011, she was invited to do a residency at the Centro de Fotografía (CdF) of Montevideo, Uruguay, from which resulted the show Río-Montevideo.

Captivated with optical obsoleted objects, this exhibit consisted in 14 slide projectors that show images taken by photographer Aurelio González between 1957 and 1973. The fascinating story of this archive goes like this: In 1973, with the arrival of the military dictatorship in Uruguay that lasted until 1985, González (during that time Director of Photography of the newspaper El Popular) gathered more than 60.000 photographic negatives he had made for the newspaper and hid them between the floors of a building in Montevideo. Soon after, the military dictatorship shot down the newspaper and this material remained hidden and then lost for more than 33 years, until it was found and finally recovered by the same photographer in 2006. Since then the negatives have been processed, restored and digitalized by CdF. When invited to do a residency, Rennó worked with this archive for almost two months.

According to the curator Verónica Cordero, “this work is addressing new ways to look at history; utilizing optical apparatus that are also on their way to be discarded and forgotten, Rennó’s work explores matters related to memory, oblivion, identity and its mechanism of obfuscation.”

Rosângela Rennó, Río-Montevideo (2011). Exhibition view at Galeria Vermelho, Sao Paulo. Photo credit: Edouard Fraipont.

Rosângela Rennó, Río-Montevideo (2011). Exhibition view at Galeria Vermelho, Sao Paulo. Photo credit: Edouard Fraipont.

Rennó in her own words:

“The story was fascinating from the beginning. The possibility to work from an archive that was hidden and latent for more than 30 years was something that I, that I’m obsessive, wanted to put my hands in and becoming part of this story. It is an archive that is loaded with history, on the most part images of the dictatorship times that feel like ghosts to me, as I lived the Brazilian dictatorship during my childhood.”[1]

Teresa Margolles, PM (2010)

Polemical artist Teresa Margolles (b. Culiacán, Mexico, 1974) strategically turned to the local tabloid PM in Mexico to collect its front pages, which portray Mexico’s drug war dead without any sort of censorship. Margolles, who began her career as an artist with the collective SEMEFO (from the Spanish acronym for Forensic Medical Service), has taken the subject of death as her principal subject since the beginning of her artistic practice in the 1980s, which combines visual arts and performance. After 2006, when violence intensified in Mexico, she shifted her focus to the violence-ridden streets of Mexico.

Margolles’ PM (2010) is a result of collecting during one year, 2010 –which was the most violent one of Mexico’s drug war until then, ending with 25, 757 murders[2]– the afternoon local tabloid PM, which circulates from Monday to Saturday in one of Mexico’s most violent cities, Ciudad Juárez. Each of the 313 covers were digitalized, framed and installed stacked, creating a grid pattern that fills the white walls of the exhibition spaces. In each of the covers there is a photograph of a murder depicted next to erotic advertisements. PM newspaper does not have a digital platform and the surplus of copies is destroyed every three months. That is why one of the most relevant aspects of this work comes precisely from compiling the daily repetition of the images of these violent deaths that would otherwise be forgotten.

Teresa Margolles, PM (2010). Exhibition view at Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria.

Margolles in her own words:

“[PM newspaper] is what you wake up to, what you hang out with, what you are reading while eating breakfast in Juárez. When you’re sleeping that is what’s happening somewhere else. It’s very popular, it works to wrap the meat you take home; you use it to make piñatas for children’s parties. Even if you don’t want to touch it, you see it. It’s impossible to avoid what’s happening in society. It’s a sensationalist newspaper but the number of dead bodies is real.”[3]

Milagros de la Torre, The Lost Steps (1996)

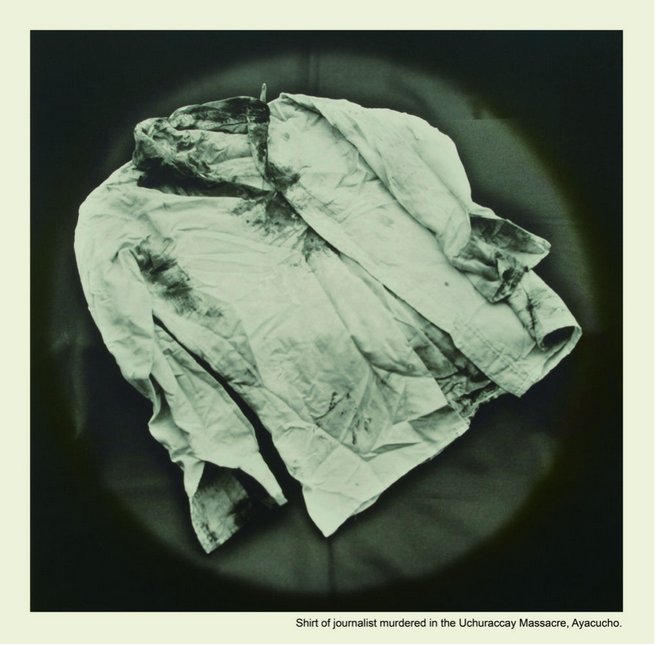

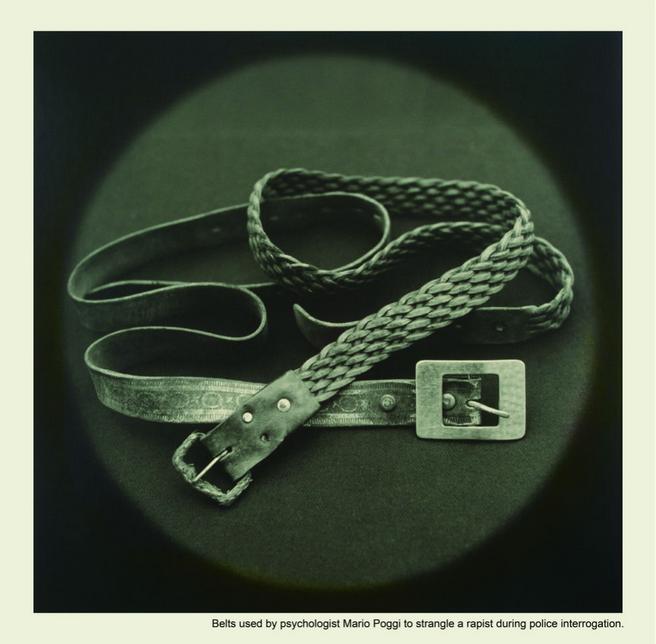

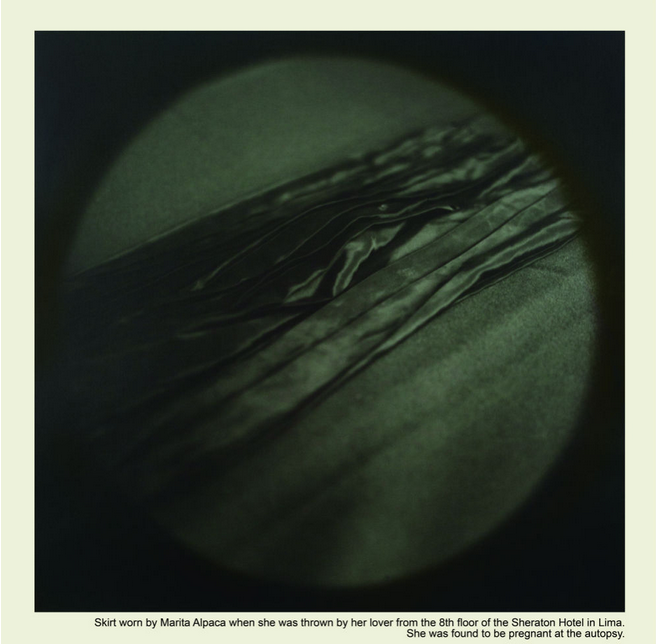

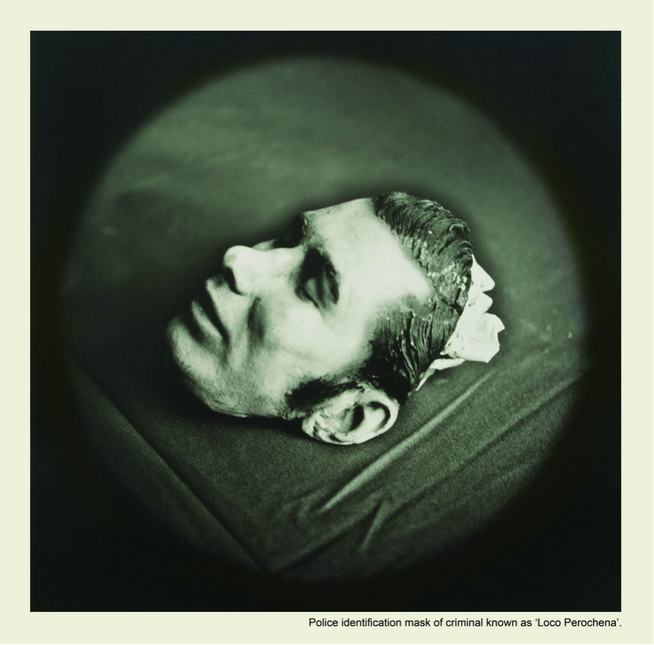

Milagros de la Torre (b. Lima, Peru, 1965), a Peruvian artist based in New York, has dealt with issues of censorship and violence for almost twenty years, focusing on the interpretation of visual language through photography. She got a B.A. in photography at the London College of Printing in 1991, and soon after (in 1993) had her first solo show titled Sous le soleil noir (Under the Black Sun) at the Centre Nationale de la Photographie in Paris, being only twenty-eight years old. Ever since she has work on what she calls “interpretative conceptual photography.” Los Pasos Perdidos (The Lost Steps) is a series of fifteen images of objects that were used as criminal evidence and are now stored at the Palace of Justice in Lima. Each image contains a small inscription that describes where the object photographed comes from, the story that each object is hiding.

Milagros de la Torre “Camisa de periodista asesinado en la masacre de Uchuraccay,” from the series Los pasos perdidos 1996. Museo de Arte de Lima.

Milagros de la Torre, “Correas que utilizó el psicólogo Mario Poggi para estrangular a un violador durante el interrogatorio policial”, from the series Los pasos perdidos 1996. Museo de Arte de Lima.

Milagros de la Torre, “Falda que usaba Marita Alpaca en el momento de ser arrojada por su amante del octavo piso del Hotel Sheraton en Lima. En la autopsia fue encontrada embarazada”, from the series Los pasos perdidos 1996. Museo de Arte de Lima.

Milagros de la Torre “Máscara de identificación policial del delincuente conocido como “Loco Perrochena” from the series Los pasos perdidos 1996. Museo de Arte de Lima.

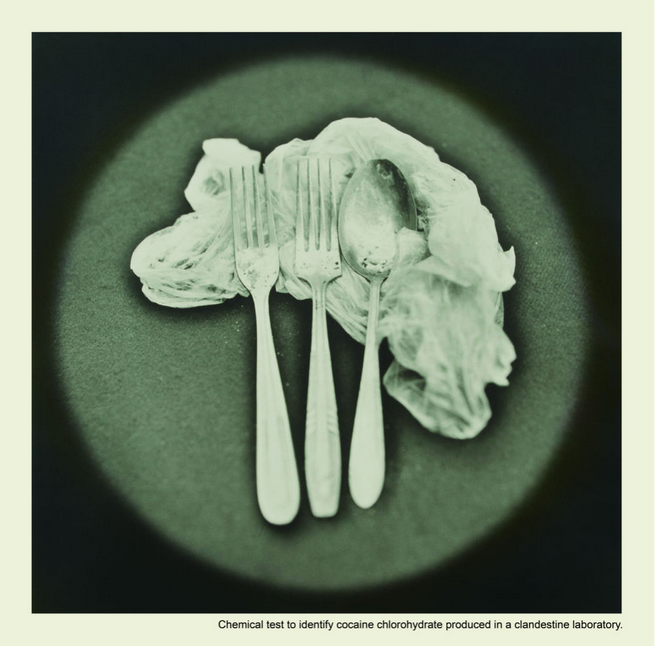

Milagros de la Torre “Prueba química de reconocimiento de clorohidrato de cocaína hecha en laboratorio clandestino,” from the series Los pasos perdidos 1996. Museo de Arte de Lima.

De la Torre in her own words:

“The Lost Steps are photographs of apparently innocent every day objects that were submitted as evidence in trials for terrorists acts, crimes of passion and other felonies. The work references a 19th century photographic technical limitation, when the development of the lens did not entirely covered the format of the photographic negative, hence creating a dark aura around the object, conferring on it a halo of mystery or emotional charge that eludes to the dark side of human nature embedded in these objects. This halo visually directs our eyes to the objects themselves. Objects are charged with human experience, and they are seen as depositories of meaning. When I was working on The Lost Steps series I carried and place these testimonial materials in front of the camera. There was an indiscernible density to them, a certain weight; they have been witnesses of some extreme event, they contain hidden crucial details. There’s a feeling that they are not just a peace of paper or a police mask but something else hidden behind. Only when one read’s a small police-like description placed under each image, is when one begins to understand when the object comes from.”[4]

[1] Taken from an interview with curator Verónica Cordero to the artist. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wpQp4EPexdk

[2] “Más de 121 muertos: el saldo de la narcoguerra de Calderón,” Proceso, (accessed July 3rd, 2014) http://www.proceso.com.mx/?p=348816

[3] Taken from an interview by Javier Díaz Guardiola. The English translation is mine. http://javierdiazguardiola.blogspot.com/2014/03/entrevista-teresa-margolles.html

[4] This was taken from Milagros de la Torre’s talk this February (2014) at SVA: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OLsB_x9R95w