of prince & the ecstasy of doing what you shouldn’t do

I try to make art which celebrates doubt and uncertainty. Which provokes answers but doesn’t give them. Which withholds absolute meaning by incorporating parasite meanings. Which suspends meaning while perpetually dispatching you toward interpretation, urging you beyond dogmatism, beyond doctrine, beyond ideology, beyond authority.

–Sherrie Levine

One of the previous assignments was met with a bit more resistance than I expected. While a lot of you readily sent me selfies, which made me more than happy, most of the people I asked to send me video of themselves saying something nice about Richard Prince just didn’t follow through. So this week, I’d like to dig myself into a hole and maybe clarify or contextualize my reason for giving out the say-something-nice-about-Richard-Prince assignment. This is a conversation that I had with a friend, Carrie Shanafelt, who is an assistant professor of British Literature at Fairleigh Dickinson University. She’s a badass with rhetoric and aesthetics and is always down to see anything.

CS – This is like analysis, you sit in the chair, and I’ll lay on the couch, and you can just ask me things, and I’ll talk.

DJ – Except, you don’t have to pay me, unless you really want to. I’ve got one of those Square readers in the corner. But the reason I wanted to talk to you about Prince was because you’ve always had interesting, daring things to say about aesthetic judgements and taste. And I’ve always really appreciated that. There’s a kindness in the way that you look–looking without needing to damn. It’s easy to take a critical stance and to just stop thinking. I’d like to believe that things are more grey and confusing. You can be critical of something and still love it, but also hate it.

CS – Part of what’s going on is that people assume that aesthetics is about value judgements, binary value judgements, and feeling superior to the work by criticizing it. It’s one way that people sort when there’s just an abundance of objects. So of course when people come to art, or even human beings, if you have too many objects in your life then you sort as many of them as possible into the category of unacceptable. The problem is that when you have work that is difficult, or that is challenging or even unpleasant, it’s going to be very tempting to dismiss. I mean, I think that we saw this in people’s responses to The Hateful Eight. It’s very tempting to say, “This movie does a lot of things politically that I find offensive. It’s gimmicky; it does a few things that are unappealing to me on the surface.” And instead of considering that as an actual challenge to their ideological assumptions, people assume that it’s a bad movie because then they don’t have to think about it.

DJ – Yeah, I mean one of the things I liked about The Hateful Eight was that it didn’t start off, this is about beauty.

[vimeo 151746651 w=500 h=281]

It starts off asking you to think about something that could not be beautiful while totally indulging in the physicality and lushness of cinema at its prime. What if this experience is as graphic and disturbing as the content? What do you do with that? I think a lot of people weren’t willing to accept that the film was ugly and disturbing for a reason. They just went off and started quoting the last bit that they can remember from the single gender studies course that they took in undergrad. “Well it’s not feminist.”

CS – “It’s racist!”

DJ – “It’s not funny anymore.”

CS – …without thinking about the ways that it was consciously playing with a lot of racist and misogynistic tropes that are taken for granted in other films.

DJ – I told you I read that Ebert review.

CS – Yeah, of Spike Lee.

DJ – He ended it with this really great line that I just didn’t expect to read from someone as boring as him. He wrote, “To an extent, I think some viewers have trouble seeing the film; it is blurred by their deep-seated ideas and emotions about race in America, which they project onto Lee, assuming he is angry or bitter. On the basis of this film it would be more accurate to call him sad, observant, realistic—or empathetic.”

CS – Right.

DJ – You could say the same thing about The Hateful Eight. We’re projecting all of this shit onto Tarantino when really it’s all just us. When we see one of his films on the screen, we’re not looking at Tarantino.

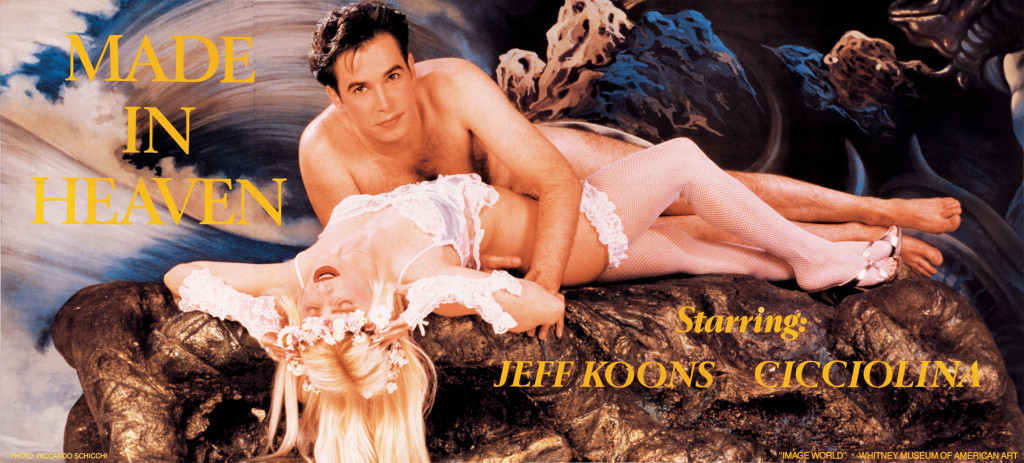

CS – Right, and perhaps the response to The Hateful Eight is that it expresses a kind of exhaustion and cynicism even more than it expresses stupidity or laziness. People are exhausted from attempting to invest themselves aesthetically in objects that have not paid them back. When I think about the reaction to Richard Prince, I also think about what happened to Jeff Koons after he did Made in Heaven; of course it’s narcissistic and self-absorbed to do pornographic work about your own relationship…

[laughing]

CS – …but he was treated like a fool by critics for a long time. But then later, Koons won people back over and they said, “Maybe we were too hasty.”

DJ – Did you see the shoot he did with Vanity Fair where he’s like butt naked working out. He’s still the same dude!

CS – Right, it’s always Jeff Koons. It’s not like there was a Koons who did Puppy, and there was a Koons who did Made in Heaven and those were different Koonses. His narcissism is part of his art, right? So is [Matthew] Barney’s. There are so many narcissistic artists. There are so many people who have nothing to say and just want to be paid attention to that I think it’s created a kind of exhaustion around people who might be trying to say something about artistic narcissism or do something interesting with it.

DJ – So, do you think Prince is a narcissist?

CS – No, I mean, to do so little with an image created by someone else, make it large and sell it–that is the art itself, as far as I understand it. The work is the process by which somebody had the guts to take someone else’s work wholesale and make it large and then take a lot of money for it.

DJ – I understand why people are angry. I mean, not really, but I can make sense of it. It’s just that I feel like we so quickly forget the history of photography which at its core has always been this cold sort of barbaric medium that is, at its best, mildly violent.

cue Sontag

To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. Just as a camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a subliminal murder – a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.

cue Barthes

The Photograph is violent: not because it shows violent things, but because on each occasion it fills the sight by force, and because in it nothing can be refused or transformed (that we can sometimes call it mild does not contradict its violence: many say that sugar is mild, but to me sugar is violent, and I call it so).

Before Richard Prince was Richard Prince the “Instagram Thief” he was “stealing” images from other photographers–this is something that he’s been doing for a long time. Rephotographing the cowboys from the cigarette ads. Painting on the rasta guy, which like he added a little circle on the dude’s face and said it was his. And let’s not forget Spiritual America from 1983 [the year I was born]. He’s been stealing shit for more than 32 years, and people are still upset about it!

There’s this graffiti artist, Kidult. He tags storefronts with these macguyveresque fire extinguisher shits. He’s the one who tagged the front of a SoHo Marc Jacobs store with the word, “Art.” Marc Jacobs responded by selling a t-shirt with a photograph of the tag on the storefront for $686. It’s like capitalism is so powerful, that you can try to subvert this image by vandalizing the facade, but graffiti is “cool.” And people will buy anything. And people did.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZmqhqKNovhw]

I think about Kidult a lot because this is someone that appeals to my inner fuck-the-man, but also because it’s someone that kind of just doesn’t get it. Sure, Kidult is, more than most, very successful at disrupting the hegemonic capitalist principles. But subversion of systems so powerful is pretty much futile. Marc Jacobs knows that. I also think Richard Prince knows it too–whether he has the same marxist rhetoric is another thing. It’s easy to assume that Kidult’s disruption is the only way to go. Loud. In your face. Destructive. Prince knows he’s a part of this system, and he’s working inside of it in the most interesting way that he can.

CS – No one is free from ideology. Satan’s obsession with “freedom” just means he knows what power is (God) but disobeys it, playing right into God’s hands

DJ – Prince is in a sense more free, and his position, I’d argue, is more important in the subversion of this ideology. Because Prince, as he’s done in the past, can use the same system that he’s fighting against to fight for him. There’s money at stake when Prince goes to court. He has very wealthy people who are invested in the legality, validity of the work. Prince’s position is more complex. And you know, I think it shows more of an obsession with photography than an obsession with himself. That’s where this all starts to get interesting because if we’re talking about narcissism, if we’re talking about images. Prince has focused in on a platform of images. You have a bunch of women who are creating an image of themselves, you know, models. They’re dealing with image as commodity. And not just women, it was some dudes too.

CS – Suicide Girls.

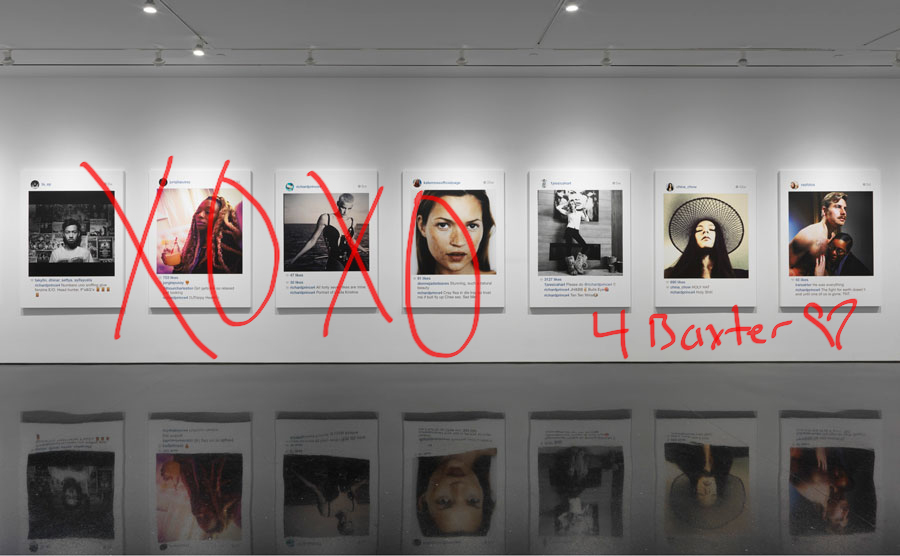

DJ – Instagram is this place where you can present an image of yourself, using images. There’s a bunch of layering. This is a space for curated content. You build an image slowly. This is something that’s been talked about whether it’s the Hipster Barbie, that live authentic bullshit, or Amalia Ulman. For Prince to take an image, which is already an image of an image and to add these quaint, almost nonsense comments or emojis, xoxo. It’s interesting. Does it need to be sold for $100,000? I don’t know. Do any of the other works from Chelsea or Midtown that sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars deserve to be sold for that much? Who cares. I’m not a gallerist. It deserves to sell for however much it sells for. This business is all speculation. There’s no actual value here. It’s an unregulated market. He doesn’t decide how much the shit sells for.

CS – Isn’t part of the feeling of outrage that it’s not a small-time person taking advantage of a big-time person; it’s somebody with quite a lot of institutional power making money as art. In the case of the Suicide Girls, these are women whose only livelihood is selling pictures of themselves looking hot.

DJ – Well I think that’s misguided though because Prince is not the one with the power.

CS – Right, it’s the gallery owners.

DJ – There’s someone behind him signing his checks. That person is the collector, the gallery owner. Those are the people with the real power. Prince knows that. So to be angry at Prince is a waste of energy. It’s like being angry at the water for being wet. He is what he is.

CS – Prince does expose some of the mechanisms of how power and money work. I think that this goes full circle to the beginning of this conversation. The problem with challenging the dominant ideology is like the problem of satire–in the old school sense, a text that deflates ideology to make it less important; satire really doesn’t ever work. In some sense, all you might ever accomplish is making the dominant ideology seem cool or funny or capable of criticizing itself and nothing changes. I’m playing devil’s advocate here.

DJ – If that was the conversation that we were having about Richard Prince, I’d be totally fine with that, but that’s not the one that we usually have. It’s about him “stealing people’s hard work.” It feels weird because I feel like I’m pretty old as far as art school goes, but even some of my students they just don’t understand that you can appropriate things. I’ve had classmates who wouldn’t post their work online because they were afraid of someone stealing it. And I’ve always thought, who cares? Like, you can’t steal an idea. If someone takes one of my images and puts it on the side of a bus in a different country, who gives a shit? It’s not like I was ever going to market myself there. I’m not a part of that economic system. I would have never been able to do that myself. If they want to do that, whatever. It happens all the time anyway. It goes back to futility, I do not believe that I can retain complete control over anything that I create. And I’m 100% OK with that.

CS – In the early 17th century, Ben Jonson claimed that the reason that he was publishing his poetry was because he knew too many plagiarists that were appropriating his work. In the poetic coteries of the early 17th century, men would get together and copy one another’s poems, and then try to take credit for them in the next group that they were in. Instead of going to the law about it, which would get him nothing, Jonson felt like making his poems visible was one way of defending himself against appropriation. I went to a lot of conferences when I was young because I wanted my ideas to be associated with me, even if they weren’t in journals yet because otherwise they were susceptible to being imitated.

DJ – You know, when the two major photographic processes were announced, the daguerreotype and the calotype or talbotype, whatever the fuck you want to call it. Daguerre gave his away. He went to the French government, they gave him a stipend, and the process belonged to the world. It was free for anyone to use, tweak, play with. Talbot, on the other hand, patented his, and said that anyone who wanted to use his process had to pay him. Technologically speaking, Talbot’s process was better. However, around the world, especially in the US, people adopted the daguerreotype because they didn’t have to pay to use it. They were trying it out, they were making it better. The technology advanced in a way that was more free. There was permission to play. Even though daguerreotypes were unique objects, they were hard to see, they were metal. Talbot’s process used a paper negative. You could make copies, the exposure time wasn’t as long, it was cheaper because paper is less expensive than metal. But Talbot went around threatening to sue everyone that used his process without paying. He wasted a lot of energy trying to protect his ideas. His idea of owning that technology really prevented it from being used, and it stopped him from being more prominent during his lifetime.

If you feel that strongly about owning something, you’re way too tied up in controlling the life of the object and you’re preventing a ton of interesting conversations from happening. Instead of us actually talking about what’s happening when Richard Prince appropriates these images, we get stuck in this really destructive loops about hurt feelings and fairness: “Is it lawful? Is it not lawful? How much money is he making that I’m not making?” A bunch of shit that just isn’t productive. The economics of this isn’t a zero-sum game. Richard Prince isn’t taking money out of the Suicide Girls’ pockets. Can we be honest and just say that, these people, however popular they think they are, were likely not on the path to selling images through Larry Gagosian on Madison Avenue [exception given to Laurie Simmons and Kate Moss].

CS – What it makes me think about is something that you brought up earlier today. The owner of the horse that photobombed a selfie that somebody is making money on–the owner demanded a share of that money. We start to get into this territory where–and perhaps this is unique to photography and recorded reality–art always belongs to the real thing in the image. If I take a picture of a person and make money off of that picture, do I owe that person? Does that person somehow, does their being become worth something economically.

DJ – In France, the answer is yes.

CS – Really?

DJ – In America, the law says that you can have no expectation of privacy on public property. So if I’m walking down the street, I’m in a public space, you can take a picture of me. I can say no, but I have no right to say no. There’s no legal consequence to someone refusing my request to not be photographed. In France, however, their laws are much more strict. A person has the right to control their image. A person’s right to privacy trumps another person’s right to create.

CS – There is no Diane Arbus of France?

DJ – I mean, there probably is, but they got sued and lost.

CS – The idea of copyright, or of intellectual property, has been on its way out for a long time but we’re watching the last hysterical death throes of intellectual property rights. Things are insane. Patent laws are insane.

[something falls in the background]

DJ – That was Earl.

[laughing]

CS – You know about the patent situation right?

DJ – I do not, my mom’s friend used to be a patent officer for a little bit, but I’m not familiar with it.

CS – So people are patenting things that they have no intention of making or doing.

DJ – Oh!

CS – …so that if anything even similar is ever produced, and they don’t even have to be that similar, they can sue. I could say that I’m patenting a drug that makes people happy when they are sad, and anytime someone creates anything like that I sue, even if I don’t know anything about making drugs. I don’t have a business, I just have a bunch of lawyers that go around threatening a people until they just pay me off to get me off their case.

DJ – I think I heard about that related to Apple. Some kind of swipe gesture that someone had a patent for. I worked for Amazon for a little bit, and they actually patented their lighting set up. Which is kind of bizarre. But you know, they are a big corporation; they have lawyers. And they thought they were the only ones that knew how to do ecom. So they patented their lighting set up.

CS – Yeah, I think that what we see now is just the last gasp of copyright law that emerged in the 19th century. It isn’t that old. It’s not defined by robust principles. And we see all these deformations of legal discourse in the service of trying to do right by the actors involved and yet still using this language that’s completely outdated, that has nothing to do with the technological and social innovations that have happened since then. Or that even existed before then.

DJ – I guess I need to clarify why I wanted people to say something nice about Richard Prince. I was thinking about how to be more positive. We’re in a weird place right now. We have all these expectations about what’s right and what’s wrong. And people are conflating morality, law, and ethics. This is what Trump has tapped into. I think that we’re all complicated. The right and wrong, the black and white, that shit is just boring. We’re depleting resources that are not renewable. We participate in systems that fuck over other human beings constantly, but we’re all ready to have a shit fit because some dude “stole” an image, an idea.

CS – We’re treating finite resources as if they’re limitless, but when it comes to ideas, which are to an extent limitless, we treat them like these precious objects that must be hoarded and protected–precious resources.

DJ – These precious resources that we will run out! When like, they won’t. I just wanted to know what it would be like, to ask people to think about what’s actually going on in these images, for a second, stop thinking about why you’re angry and try to see Prince in a different light. I’ve changing the way I approach art. I’m not interested in establishing right and wrong for art. What things should be done or shouldn’t be done in the name of morality or law. Those standards change and vary all around world. Like today, right now in New York city, it’s completely normal for a grown man to put a newborn’s penis in his mouth. Even though it’s illegal, there are families that request these old men to suck their baby’s dick. You know, if we’re talking about law, it wasn’t that long ago that interracial couples were illegal. It really wasn’t that long ago that same-sex marriage was illegal. And there are still a ton of places around the world where sodomy can get you killed. I think in art, I don’t want to participate in an art world where we become so obsessed with what’s right or wrong that we actually start policing what can and cannot be made. Imagine if scientists obeyed morality more than their own curiosity?

I don’t know, I just want someone to surprise me. Tell me that there’s another way to appreciate this work. It’s easy to have a conversation about him being a powerful white man stealing the images of young white women but really, especially for me, that’s already boring. White people steal shit. I understand that. This is a conversation that is not new to me. How else can we talk about this?

CS – Your request for people to say something nice, wasn’t to affirm the work or even say it’s good work. But it was to find something that was not quite so vehement or damning. That the impulse is to damn. This is why I started thinking at the beginning of the conversation about the way total disgust, ideological purity, and all these things become ways for us to sort out and say, “I don’t have to care about any of these things because it doesn’t fit my ideological purity on some topic.”

DJ – We both love hating things. I’m not against hating things.

CS – Yeah, we’re good haters.

DJ – What if you don’t hate it? I try to challenge myself, especially with art, to figure out why I don’t like it. I think I owe it, not to the artist, but to myself to figure out what’s actually going on behind the initial reactions to an object before I dismiss it.

CS – And is it a kind of aesthetic choice, to say that this is bad? Like, I’ve heard you say, “These are bad photographs; they are poorly taken.” In which case, you’re likely not that inspired to spend more time considering the object. But when you walk away from a work of art and you say, “This makes me mad; it troubles me,” maybe it’s worth doing something other than relegating it to the dustbin of bad work.