Public Image

A theory: photography alone has the potential to turn the public art museum into a community space. What I mean is that photography, unlike any other medium featured in the art museum, is a field of action where the artist and the viewer can convene: within the museum, there are photographs that have been taken by “artists” on the wall and there is also the potential for visitors to make photographs. We could call both these activities, together, museum photography. I got to thinking about this again because of the current exhibition of Eugene Atget photographs at MoMA, entitled “Documents pour artistes.” The title is borrowed from a sign that hung outside Atget’s studio, which was meant as a sort of proto-artist’s statement meant for all those who entered Atget’s studio: welcome, here are some images you might find some use for. The problem is that MoMA has little interest in actually recreating the ethos of Atget’s original sign: the use of a camera inside the show, like in all other MoMA exhibits, is expressly forbidden*. It’s beyond ironic, it’s manipulative and condescending: MoMA wants to have it both ways.

They want the reputation of being a progressive, arts community that not only exhibits edgy work but brings their savvy audience into that fold. But the last thing MoMA wants is to actually engender a space where the traditional lines between the people who get their work on the walls and those who come to look at it can be blurred. Jesus, just think of the legal liability, alone. You can’t have people groping Marina Abromavic’s nude performers all willy-nilly, like they’re in on it; no, what you do is let them cool their heels on a 5-hour line first, then they can sit in silence for a few minutes across from the artist. MoMA, like most museums, cares primarily about their public image, not images belonging to the public.

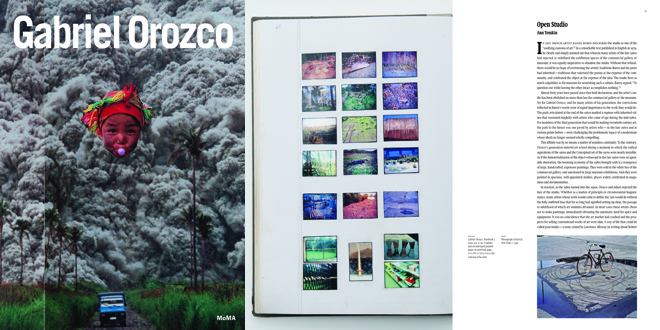

This was made painfully, hilariously, clear to me two years ago during MoMA’s 2010/11 Gabriel Orozco retrospective. The main gallery for the exhibition had been wrapped in a blow-up of a photo collage from one of Orozco’s early journals (it was also the cover image for the show’s catalog). The original images in the collage were taken from various National Geographic photo-essays. I dare anyone to show me a documented case of an artist obtaining proper licensing rights to paste some cut-outs into their journal. The photo was pretty clearly an act of so-called “appropriation” art, a century old genre of treating the wide world of images as a public trove for source material (like how Atget imagined his studio should work). And standing right smack-dab in front of the blow-up is that trusty old MoMA stanchion crowned with a little icon of a camera with a red slash through it bearing two words: PHOTOGRAPHY PROHIBITED. The message was clear. Orozco can make illegal copies of images and it’s art, in fact we’ll pay him to do it. But the general public better not get any ideas- those rules don’t apply to you; the best you can do is pay us for a book of these images, and then don’t forget to read the copyright license on the first page which tells you that you still can’t do anything but look. Come on, what do you think this place is? Did you think it was invented to collect a bunch of objects and images all for your sake?

Now there are lots of things artists are given the privilege to do in a museum that audiences are not, and lots of these asymmetries make a lot of sense: the artist Fred Wilson is allowed to re-arrange the museum’s permanent collection; Michael Asher is allowed to demand the museum stay open for 24 hours; I’m sure somewhere a museum has let Kanye West turn a gallery into a night-club. There’s no practical way to let everyone engage with the public space of the museum in these ways, and beyond that there isn’t a convincing political or historical rational for it either.

But I want to make the argument that photography is a special case. For a number of practical, political, and historical reasons photography is a field of activity where museums could and should allow artist and audience to converge and partake in a shared wealth of images and techniques. The public museum was in fact founded as a fiduciary for the general public and photography remains the most feasible way of realizing that historical commitment. In the following posts I’ll make this case in more detail and then I’ll look at a recent bizarre attempt by a museum to defend itself against photographic reproduction that ended up with them unintentionally producing an ingenious piece of conceptual art.

*edit: as a colleague pointed out to me, this is inaccurate and needs clarification: the use of still, non-flash photography for “personal use” in collection galleries is permitted at MoMA. “Personal use” would exclude using any photographs for (publicly and/or commercially) displayed artworks; for this reason, I would argue that “personal use” is a serious blunting of Atget’s “pour artistes”. The contradiction remains for the Orozco show, and all non-collection exhibitions. And the original argument, that museums like MoMA proscribe an unreasonable asymmetry towards “museum photography” vis-a-vis artists and viewers, still holds and will be borne out more clearly by the following analysis.