Review of Nandita Raman’s exhibition “Body is a Situation,” by Phil Taylor

Our body is more elastic than we think. Teasing, pulling, receding, absorbing the welter of forces that press towards it, splitting off into pieces, coiling in upon itself, endlessly deforming and reforming itself, informed by all in its surround.

How large the surface of a foot is, I think, as I face up the first work encountered in Nandita Raman’s recent exhibition, “Body is a Situation.” Not quite gigantic, yet not quite familiar, the three pictures each frame a vermillion impression of the sole of a forefoot or the pads of the toes, each different in scale, each paper sheet different in size, dancing around an invisible center point on the wall. A footprint expresses the contact zone between the body and its physical grounding in the world. This work–is it drawing or painting or photography or all of these?–lays out the thematic chords of Raman’s show. For Red Feet (Triptych) simultaneously foregrounds and destabilizes the fleeting traces that demarks one’s location. The images initially offer the illusion of immediacy, which is equally undermined by the distancing effect of abstraction. Abstracted because, despite the indexical nature of body prints, this picture is a reproduction, the original impression enlarged, scaled up, expanded to defamiliarize this malleable, elastic body.

The exhibition was composed of disparate marks and signs, slipping across and hybridizing mediums: Photographs, drawings, texts, all pinned to the wall, variously representing a journal, a body print, sculptures, books, and tightly framed architectural forms. The underlying subject is Varanasi, the city of the artist’s birth. A city I have never visited, indeed thousands of miles from any ground upon which I have ever walked. And yet I have an image of this city already, conditioned by hundreds of photographs, cinematic views, tourist postcards, and literary romaniticizations of the historical city on the Ganges: the steps rising from its banks, the rituals of daily ablutions, the funeral pyres.

None of that is pictured by Raman.

In fact little of what is depicted could be said to capture the city through genres of representation that conventionally signify place and location. No landscapes, no architectural studies, no street scenes–nothing that would lend itself to the tourist postcards or the immediate identification of eager gazes wishing to confirm what they already think they know.

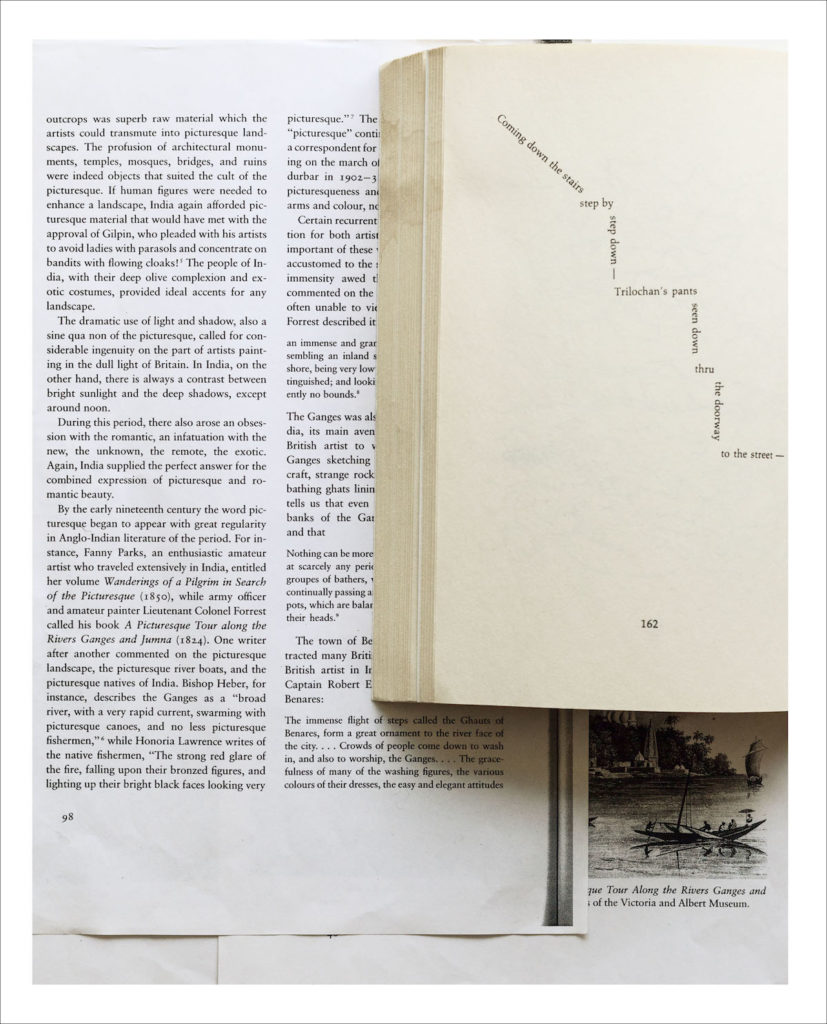

The significance of this refusal is brought home by Picturesque, 2017, an overhead photograph of layers of printed text: An open book, Ginsberg’s Indian Journals, reveals a concrete poem describing the descent of a staircase, the vectors of its lines of verse visually mimicking the zigzag of irregular steps, the poet’s enjambments drawing the fall of footsteps. Ginsberg’s volume partially obscures several overlaid photocopied sheets. The poet’s image of the staircase recurs in the academic text through the quotation of 19th-century British captain who exalts before “The immense flight of steps called the Ghauts of Benares [sic].” This art history describes the romantic exoticization of India in which British representations framed the colony to discipline it under the aesthetic paradigm of the picturesque.

Staggered this way, Varanasi’s construction through the European and American cultural imaginary archive is re-formed as a collage within Raman’s photograph. The discourse itself becomes a subject for photography, to be studied, arranged, composed before the camera, offered as subjects of attention. But the tradition that they stand for is resolutely rejected. This genealogy of white men’s exotic fascination with Varanasi, and their program of capturing it as an object of delectation within their pictorial and poetic paradigms is re-framed for what they are: projects of the colonial imaginary. More than that, perhaps, they are framed as accretions of preconceived ideas, mythologies in their true ideological function.

Between the body and a city: That is where Raman situates the conceptual frisson of the exhibition. “I’m moving through the city, wishing to reclaim it, to make this heady and almost mythical place my own,” Raman writes, her text pinned aside her pictures. “How do I experience my body as I traverse this metropolis full of female deities but where women are conspicuously absent from public spaces?” Maha Maya, a diptych, shows a temple offering of garlands and petals. In one picture, hands reach into the downward frame, sweeping back the drape of silk garments to reveal the feet of a deity. The understanding of the body is posited as a dynamic practice of mimesis and recognition of culturally determined figurations. Artwork and the embodied self engage in a relay of formation and alteration.

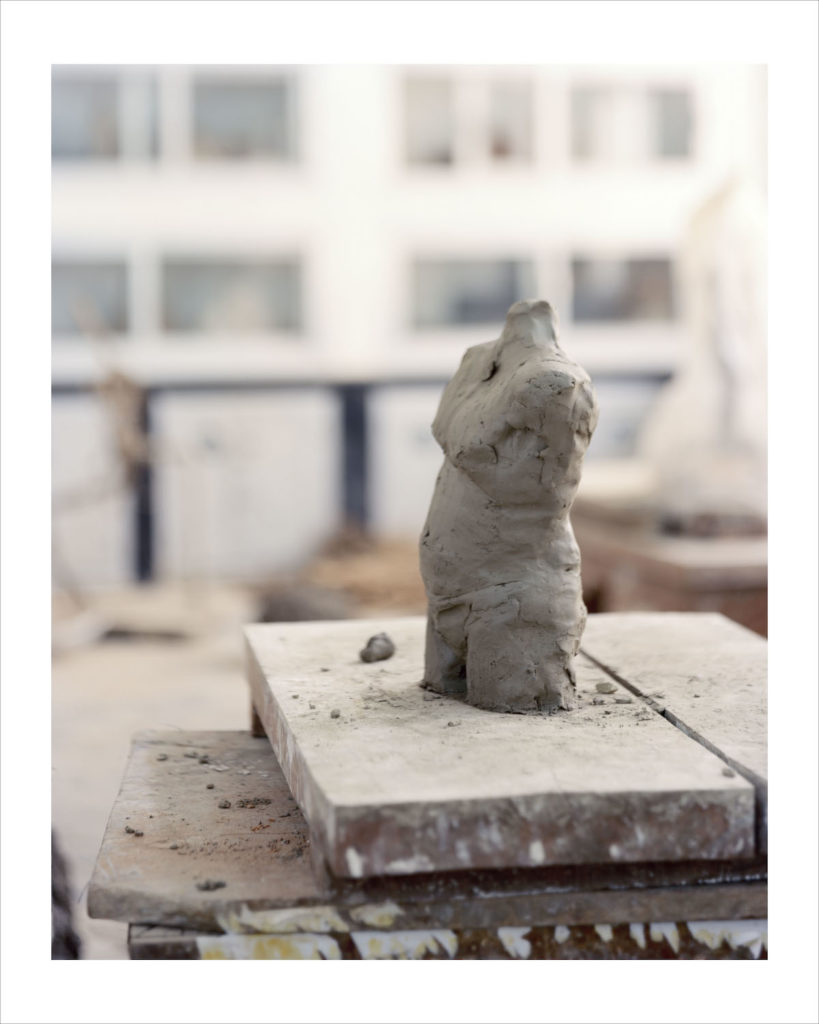

This concept was expanded and refined in two photographs of wet clay torsos, truncated of all appendages: one de profil, one de face–only missing de dos to complete the classical poses. Still, even seen in these nearly identical forms, it is not clear that the sculpted figure in each photo is one and the same. Raman’s shallow depth of field obliterates any peripheral detail. What matters is what is close to the figure. A sense of its material, and its position.

What is commonly known as culture is perhaps less elastic than a given body. But it does give, bend, and mold in response to changing values and the dynamic pressures of history. Representations and rituals are reservoirs of history–perhaps, what anthropologist William Mazzarella has called the mimetic archive, a repository of practices, like those techniques of the body passed on through generations. To locate the possibilities of one’s own body requires perception of an existing social matrix. But those guidelines are not absolute.

Raman makes clear that the body’s situation is not precisely geographic, nor confined to position or locality. Situation is a contingency. Raman’s drawings map the contours of the feet. Outlines, seen from above, doubled, as if following or proposing a step aside, a second position. A mark, perhaps a scar, atop the right foot. I think of my own scar, on top of my own right foot. Another drawing of a foot, seen in profile, again twice. The second time, with studiously delineated epidermal ridges and sweat glands filled in, giving depth to the form, and an unexpected intimacy in looking so closely at another’s foot. It is difficult to see one’s own foot in profile.

“The body is a situation.” The concept is Simone de Beauvoir’s, who, in The Second Sex, declares, “if the body is not a thing, it is a situation.”(1) The the body is reformulated as always already culturally formed and embedded within a social matrix. For Judith Butler, the consequences of this redefinition serves to denaturalize the body as reducible to binary distinctions of sex, and furthermore to conceptions of gender that claim to be essential and absolute categories. The body’s situation is constructed repeatedly, constantly, over and over again through myriad performances and impositions, the projections and rejections that inscribe the body of the subject within the space of the social.

Searching for another figurative model on which to understand the gendered construction of the city, Raman turns her camera to remark another language of forms through which to situate the body in Varanasi. Anatomy undergoes a graphic process of abstraction, translated to circular forms that Raman reads into urban topography and geological formation as signs of a navel and a vagina. Towards these drawn and carved forms, the situation of a body located in or known through Varanasi might be re-oriented through the conceptual machinery of the exhibition.

As this meandering account has sought to sketch out, Raman’s drawings and photographs conscript religious iconography, colonial politics, cartography, the intimacy of daily experiences, and the recursive practices of reading, writing, and walking. To view the images and unpack their citational politics is to follow Raman as a reader. In the exhibition, I, the viewer-reader, follow her nimble body-gaze. Competing systems of representation collide, brought into dialogue in order to tease out their respective inadequacies. Photography serves as a means of annotating and sharing the practice of reading and researching, and then of projecting one’s knowledge and experience back into the world, to see it anew, as transformed by the experience of–and rejection of–this archive. Raman posits this action of processing within the figural possibilities of the exhibition, as references and competing forms aggregate between visually disparate works. From the outset, the body’s situation is constructed within and against representation. Yet even when imprinted on a solid surface, the image of the body is not singular: Raman’s use of the device of the diptych and the triptych structures the exhibition, so that signs and bodies are never fixed by a definitive representation, whether drawn or photographed. A figuration is constructed in parallax. Reading becomes dancing. The body is nimble.

(1)“[S]i le corps n’est pas une chose, il est une situation.”