Photography Exercise No. 1

I have developed a few exercises that I feel were very beneficial to my photography and to my understanding of the field. This is the first such exercise and I will post more in the coming weeks.

For this exercise, pick a favorite photographer and pick five of their images that you really enjoy. Write a short paragraph about each one. You may like a photograph because of how it strikes you visually, but you will always find that there is more there when you start to describe it, even to yourself. Writing about photographs is a great way to go deeper into the work of a photographer and to better understand their vision.

I picked Walker Evans and here are the five photographs and the short paragraph I wrote for each. Keep in mind that this is just an exercise for yourself. This doesn’t have to be scholarly or technical, it’s just to get us seeing on a deeper level and getting lost within the picture plane. There is additional information about Walker Evans at the end of this post. Enjoy.

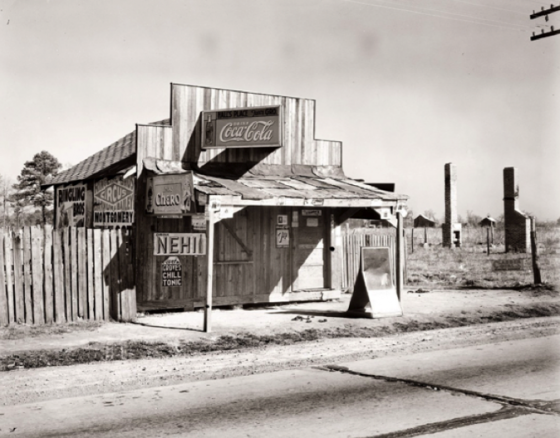

This ramshackle tumbledown store barely ornaments a desolate paved and patched country road in the deep south of Alabama. The sidewalks are unkempt and unwalked. Unaffiliated chimneystacks litter the abutting barren field like monuments of failure. Rough-milled wood slat fencing ostensibly protects seemingly nothing worth protecting. You can feel the harsh sunlight beating down on the patchwork roof as it refuses to set. Advertisements for simple pleasures – sodas and circuses – adorn the shanty only slightly more effectively than a carving on a tree stump, only with not half the charm. The power lines visible in the top right corner of the photograph bypass the shack altogether, wholly negating the concept of refrigeration or any notion of electric lighting.

Woodlawn Plantation

Belle Chase, Louisiana 1935

If ever an edifice could be crestfallen, it is this one. The Woodlawn Plantation house manages to embody a tired Stoicism, exhausted and undone by both nature and man. The fluted Ionic columns sag under the weight of a warping entablature. Successes are married with excesses and triumphs wedded with follies. Ceremonially and unnecessarily boarded and solemnly and necessarily forgotten, the slats of the shutters are giving up one by one along with the shingles, following a banister that relented long ago to the torture of abandonment. Ivy envelops the eaves of the front-gabled afterthought side chamber. Unsown crop rows insult a lawn that ought boast a bowling green and ornamental gardens. Street front property. Only one previous owner.

Mayor’s Office

1936

Iron barred windows of an upstairs jail. A sweltering holding cell for the town drunk or a mendacious transient, a structural crack spoiling the cosmetic stuccoed exterior of the mayor’s office starts the decay of this rural suggestion of a government building with the hand-lettered indication redolent of an old west ghost town. A fire has charred and colored the collapsing blocked concrete add on that adjoins the pseudo-monolithic structure, but has failed to engulf and overtake it completely. Repurposed train cars improvise livable spaces. A Model A Ford litters the adjacent un-mown field. A slanting horizon adds to the desperate unease and feeling of a slow suffocation. A puddled road halfheartedly reflects what once was.

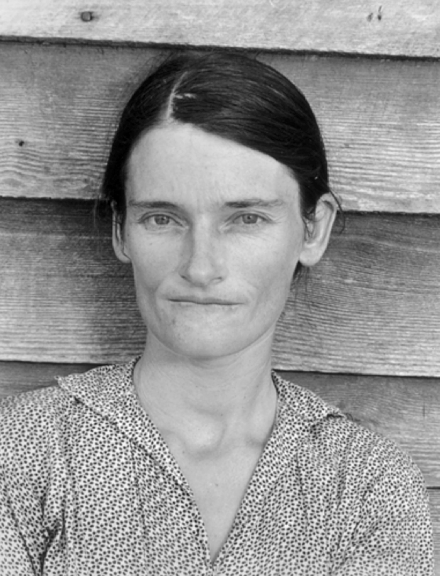

Allie Mae Burroughs

Hale County, Alabama 1936

The photograph of this tenant farmer’s wife reads as a God-forsaken icon of The Great Depression. All of the evidence of a life hard lived lies in her elderly-from-a-young-age face and piercingly ignorant eyes staged before the simplest of wood sidings. The slightest patch of missing hair is further testament to hardship. Still, a non-frown is sometimes a smile, and we find contentment and appreciation despite penury.

Bud Fields & Family

Hale County, Alabama 1936

Pseudonym Thomas Gallatin “Bud” Woods

An homage to destitution, a malnourished cat lies under an iron bed by the dirt caked feet of the Fields family. A paucity of possessions is a photographic treasure chest. The dirt covers their clothing better than the wood floor covers the dirt. The unconvinced grandmother, in her stockings that aren’t worth pulling on, looks wary, but too tired to protest. Behind depleted faces remains a semblance of togetherness and contentment. The scarcely clothed toddler seems oblivious to the reality of his existence, while his slightly older sister stands where self-awareness selects detachment.

More on Walker Evans:

Walker Evans was born into an affluent family in St. Louis, MO in early November 1903. His parents’ wealth afforded him an education at the prestigious Phillips Academy in Andover, MA, and from there he proceeded to Williams College, where he studied French Literature before dropping out after his first year. Upon separating himself from formal academic studies, he traveled to Paris for a year, before returning to the states and settling in New York City, where he quickly befriended the most esteemed members of the art community. In 1928, at the age of 25, Evans got his first camera and began photographing in earnest. Only a few short years later, in 1933, he landed his first major assignment – photographing for Carleton Beale’s book, The Crime of Cuba, which documented the revolution aimed at overthrowing then dictator Gerardo Machado.

Evans’s next big appointment was shooting in West Virginia and Pennsylvania as a staff photographer for the Resettlement Administration, a project of The New Deal designed to relocate struggling rural families to planned communities. The project was renamed and reorganized less than a year later due to some members of congress alleging that President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s endeavor in this sphere amounted to Socialism. The restructured program was called the Farm Security Administration, which, in part, intended to document the effects of The Great Depression, with Evans’s work focusing mainly on the rural south. Most of his work form this time was shot with a large format 8×10 camera.

In 1936, while still on duty for the FSA, Evans accepted a freelance assignment from Fortune Magazine documenting the lives of three white tenant families in rural Hale County, Alabama to complement an article to be written by James Agee. The magazine later scrapped the piece, but in 1941 the work was published in book form with the title Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. The project was envisioned by Agee as a three-volume set, with each tome being “an independent inquiry into certain normal predicaments of human divinity,” but the two intended sequels never came to fruition. The photography in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a reference to a verse from Ecclesiastes, details rural poverty in stark detail. The wealthy landowners told their tenants the journalists were Soviet Agents in an attempt to dissuade them from allowing themselves to be photographed and reported on.

Evans continued to work for the FSA until 1938. That same year, the Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibited Evans’s work in it’s first ever show of a single photographer, while simultaneously publishing the catalog American Photographs. In 1945, Evans became a staff writer for Time Magazine, and soon after became an editor at Fortune, holding that position until 1965, when he become a professor of Graphic Design at Yale University. Shortly thereafter, Evans became the first professor of photography at Yale, teaching until his death in 1975. Lincoln Kirstein, General Director of the New York City Ballet and personal friend of Evans’s, said of his photography, “It is…the naked, difficult, solitary attitude of a member revolting from his own class, who knows best what in it must be uncovered, cauterized and why.” There is an understanding in his photographs that marries acceptance with incredulity, without ever feeling the crossing of a boundary or any personal imposition by the photographer himself. The images show a truer reality of the country than any before or since, and there is no better title for this collection of Evans’s work than American Photographs.