you are unsheltered, cut with the weight of wind

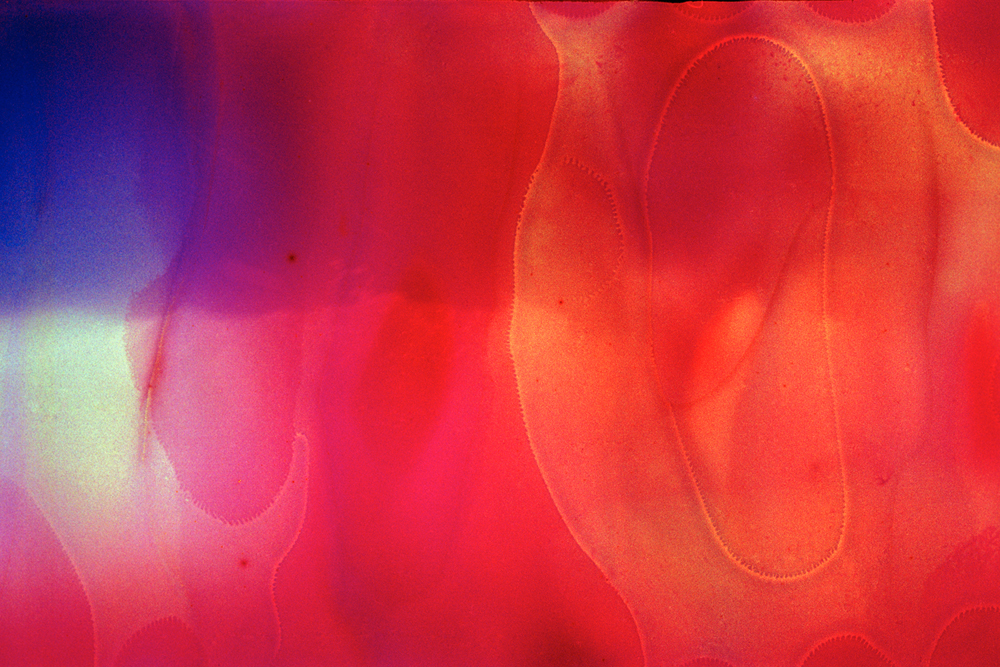

Above image: Dillon DeWaters, from the series Ocean/Ocean, 2010

you are unsheltered,

cut with the weight of wind—

you shudder when it strikes,

then lift, swelled with the blast—

you sink as the tide sinks,

you shrill under hail, and sound

thunder when thunder sounds– H.D. “The Shrine” from Sea Garden

The sea, the sea.

Perhaps it is because we are surrounded by water from the moment we emerge – is it a pop? a burst? a transformation? a transfiguration? – from non-existence to existence, from no-breath to breath, we all come into the world this way, surrounded by the waters, hearing echoing voices amid a rush of fluid, still, fast-flowing, gurgling with air.

I grew up near the sea, was rarely more that five miles away from it at any given time, and have never spent much time far inland. The sea is an ironic comfort – that sublime and terrifying body – but, nevertheless. The sea is hugely occupying for so many artists across time, visual artists, writers, dancers, musicians. The way the sea holds, reflects and carries light, its sounds, its relationship to memory. One summer, my husband, the artist Dillon DeWaters, carried his camera into the waves and let them wash away layers of film emulsion as he shot away – an existential exercise, to see what if anything would survive. Let’s even expand this idea to other bodies of water, to rivers, lakes, bays, harbors, even puddles. Some are still, some roiling, some rushing, some comforting, some a horror.

Virginia Woolf played the sea into her narratives as a player ever in the present. That is, the sea is so of the now, so happening exactly in time that it causes us to gasp in our realization of our own imminent future, of aging and death, the sea becomes an avatar for that particular nostalgia-for-the-present that seems to happen most particularly in the summertime, but also, even more harshly, perhaps, in the other seasons. The waves of the sea are a constant reminder of time’s unapologetic march into the future, driven by tides, guided by lunar cycles, high to low and back again. I think, too, of Woolf’s future (that is, once the future, then the present and quickly the past), filling her pockets with stones and walking into the River Ouse to create an ending. At the outset of The Waves she writes (in the present, as though she is always writing):

The sun had not yet risen. The sea was indistinguishable from the sky, except that the sea was slightly creased as if a cloth had wrinkles in it. Gradually as the sky whitened a dark line lay on the horizon dividing the sea from the sky and the grey cloth became barred with thick strokes moving, one after another, beneath the surface, following each other, pursuing each other, perpetually.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Boden Sea, Uttwil, 1993

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Boden Sea, Uttwil, 1993

This slowly appearing and disappearing line of the horizon leads me to think of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Seascapes, a series that sets the concept of time in the foreground. Beyond the obvious aesthetic sensibility of the images – we can’t but help feel something in response, they are beautiful, serene, sublime, the silver gelatin prints themselves luscious in their perfection of whites and greys and blacks – there is also a clear connection to the pre- (or post-) history of humankind. These “landscapes” could represent the earth 200 million years ago or 5,000 years into the future. They truly present time – several hours of exposure – and yet also exist utterly outside of time, could be any time, any place, on this planet that is covered 71 percent by water.

I spend my July on an island which smells of sea and honeysuckle and privet – sweet and salt – and am continuously conscious of being surrounded by water. The sea plays a central role in daily life here, my days spent working punctuated by long swims in cold, salty water. This one-twelfth of my year – which combines intense work and daily negotiations of currents and fish, sand, stones and salt – somehow shapes the remaining eleven-twelfths. Without this, taking away this month of daily baptisms, I am a different person.

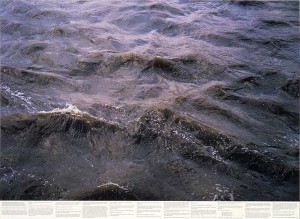

Roni Horn, [no title] from from Still Water (The River Thames, for Example), 1999

Roni Horn, [no title] from from Still Water (The River Thames, for Example), 1999

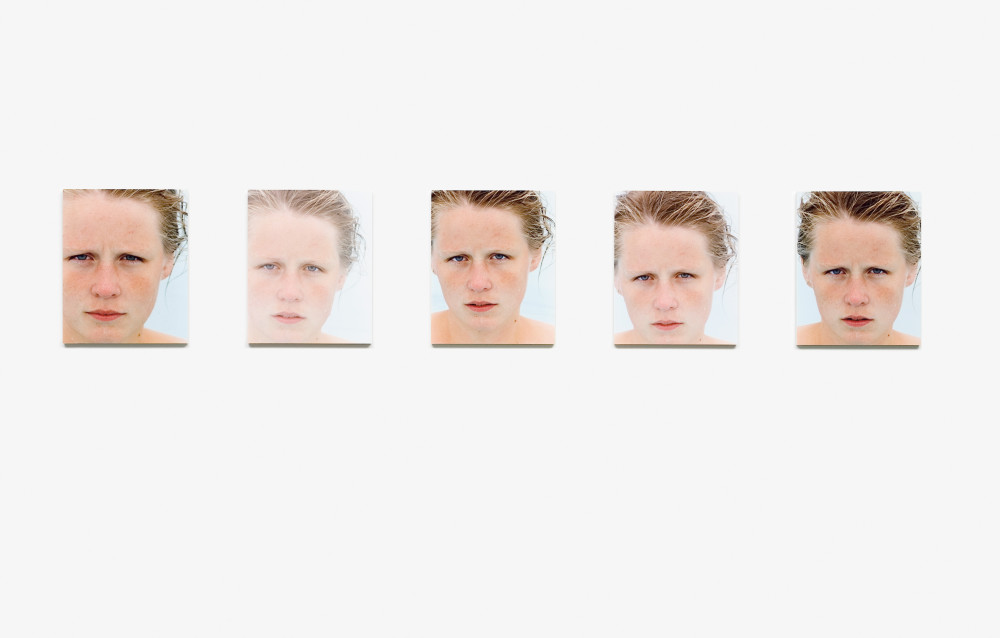

Roni Horn has a vibrant relationship to water. I think in particular of Still Water (The River Thames, for Example) and You Are the Weather. In her PBS Art21 segment (from Structures), she describes her relationship to her practice as one in which “I like to keep my feet in the moving water” and describes water itself as “everything and nothing,” going on to say, “I almost feel like I rediscover water again and again.” She discussed being drawn to the Thames (a river guided by tides, which rises and falls up to 24 feet in places), not just because of the “visual darkness” of the waters but also “a psychological darkness,” in the Thames’ role as the most appealing river to foreign suicides. You Are the Weather presents “a person as a multitude,” the same person, always partially immersed in water, confronting the viewer directly. This is an erotic gaze, full and yet ambiguous. Interestingly Horn describes her photographs of the Thames as portrait and the portraits of the subject in You Are the Weather in these terms: “I was curious to see if I could elicit a place from her face, almost as a landscape.” I find these contradictions exciting. As Horn concludes the interview: “You use metaphor to make yourself at home in the world. You use metaphor to extinguish the unknown.”

Roni Horn, detail of You Are the Weather, 1994-1995, 36 gelatin silver prints and 64 chromogenic prints, 10½ x 8½ each. Detail from the 2009-2010 exhibition Roni Horn aka Roni Horn at the Whitney Museum.

Roni Horn, detail of You Are the Weather, 1994-1995, 36 gelatin silver prints and 64 chromogenic prints, 10½ x 8½ each. Detail from the 2009-2010 exhibition Roni Horn aka Roni Horn at the Whitney Museum.

Finally, I was struck quite recently in the new Met Breuer’s exhibit, Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, by J.M.W. Turner’s very late seascape paintings. These are unfinished or ambiguous, quiet or screaming. Something about these paintings – I cannot pinpoint quite what – seems out-of-time, more akin to avant garde music, perhaps, as they float between abstraction and pure perfect representation – the feeling of the sea.

J.M.W. Turner, Rough Sea, c.1840–45, oil on canvas, 91 × 122 cm

J.M.W. Turner, Rough Sea, c.1840–45, oil on canvas, 91 × 122 cm